|

Amazon’s Q2 2014 earnings report brought a triple whammy of disappointment to impatient investors:

Three chronic concerns underscore growing investor unease with Amazon’s management priorities:

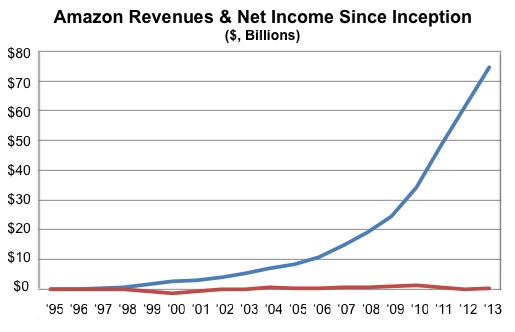

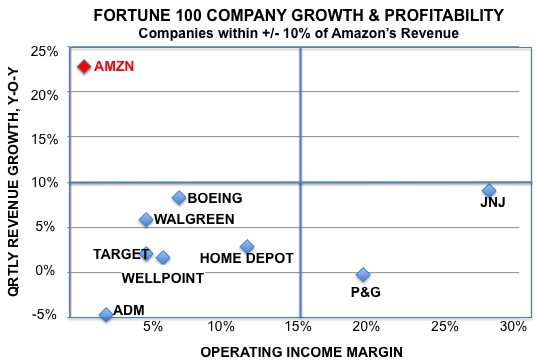

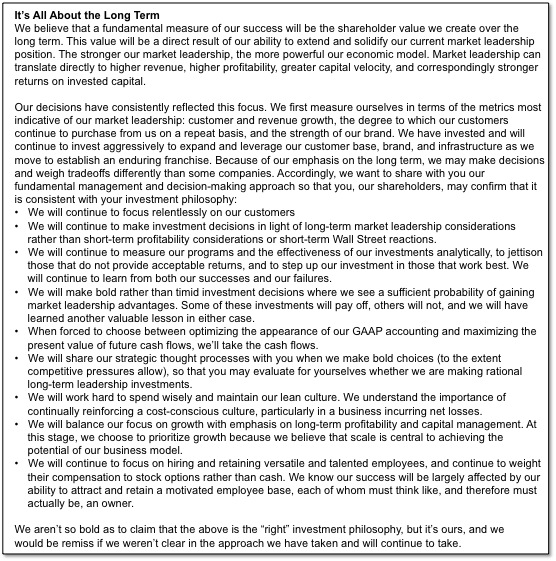

Jeff Bezos’ Guiding Principles Bezos built Amazon on the foundation of being stubborn on vision, but flexible on details. And no CEO has ever been so clear in articulating his corporate vision as Jeff Bezos, who laid out the company’s guiding principles in his first letter to shareholders in 1997. In that document (which Amazon has included in its Annual Report every year since), Bezos signaled his intent to build a company focused on long-term growth, bold action, market leadership and customer satisfaction. As if anticipating the current criticism, in 1997, Bezos cautioned: “Because of our emphasis on the long term, we may make decisions and weigh tradeoffs differently than some companies.” He has been admirably, and to some, frustratingly true to that vision ever since. In this context, let’s examine each of the sources of investor angst in turn. The time is long overdue for the company to deliver profits Echoing the concerns of many analysts, Michael Yoshikami, CEO of Destination Wealth Management (which sold its stake in Amazon last year) recently noted: “Most companies with the kind of gross revenue Amazon has are not posting these kind of losses.” Well that’s an understatement! To put Amazon’s recent financial performance in perspective, consider the figure below, which displays revenue and net income since the company’s inception. There should be little doubt that Amazon has been reinvesting operating profits to fuel future growth. And its growth rate has been extraordinary. From 1995 through 2013, Amazon has grown its topline at a compound annual growth rate of 94%. Granted, growth rates have slowed as the company has bulked up, but Amazon is on track to be the fastest company in history to reach $100 billion in sales. With current revenues of >$75 billion, Amazon reported 23% topline growth on a year-on-year basis in its Q2 results. As noted below, comparing Amazon to companies that are within +/-10% of its current revenues, Amazon’s topline growth rate is in a class by itself – as is its lack of profitability! In its relentless pursuit of growth, Amazon has become over-extended Amazon’s profitability has undoubtedly been dragged down by its frenetic pace of investment in new businesses. As Jeff Bezos noted in his official statement accompanying the company’s Q2 earnings report: We’ve recently introduced Sunday delivery coverage to 25% of the U.S. population, launched European cross-border Two-Day Delivery for Prime, launched Prime Music with over one million songs, created three original kids TV series, added world-class parental controls to Fire TV with FreeTime, and launched Kindle Unlimited, an eBook subscription service. For our AWS customers we launched Amazon Zocalo, T2 instances, an SSD-backed EBS volume, Amazon Cognito, Amazon Mobile Analytics, and the AWS Mobile SDK, and we substantially reduced prices. And today customers all over the U.S. will begin receiving their new Fire phones — including Firefly, Dynamic Perspective, and one full year of Prime — we can’t wait to get them in customers’ hands. Each of these ventures requires startup capital that may take years (if ever) to recoup. As Amazon’s cash from operations has grown over time, it has accelerated its investment in new business development, venturing further afield from core ecommerce retailing to compete in the markets for tablets, smartphones, cloud computing, streaming media and original television content. S&P Capital IQ analyst Tuna Amobi (who has a sell rating on Amazon) summed up the sentiment of many in noting: “There’s a lot of stuff they’re doing that’s questionable. There’s nothing wrong with spending to diversify your business, but it has to be in a focused manner as opposed to throwing spaghetti on the wall and seeing what sticks.” The company’s obsessive secrecy manifests a blatant disregard for shareholders, which stands in stark contrast to its customer attentiveness From the company’s founding, Jeff Bezos has been unwilling to divulge financial performance at the business unit level. This has set up a cat-and-mouse game between Amazon executives and industry analysts striving to learn more about company operations. For example, analysts have struggled for years to gain more insight into how many Prime customers Amazon has enrolled, or how many Kindles, Fires, hardcovers or ebooks it has sold, or how much AWS revenue it has booked or how much investment it has made in streaming video. But Jeff Bezos doesn’t like to get specific with numbers. For example, When Bezos took the stage in June to announce the launch of the Amazon Fire smartphone, during his 90-minute presentation, he took the opportunity to drop hints about the company’s broad-based business impact using the deliberately vague terminology: “tens of millions.” Here’s a sampling from his presentation:

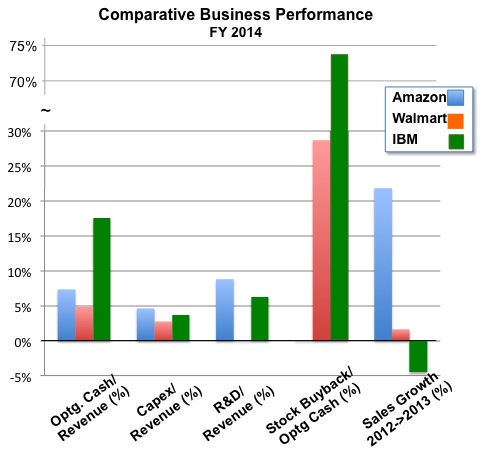

Bezos’ catchphrase is reminiscent of astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who popularized public awareness of astronomy with his frequent reference to the “billions and billions” of stars in the intergalactic universe. The difference of course is that the phenomenon Sagan was referring to is truly unknowable, whereas Jeff Bezos knows precisely how individual components of his business are doing. But that’s for Bezos to know and others to guess. Care to speculate how many Kindles Amazon has actually sold? From Bezos’ opaque tease, the answer may be 20 million and growing or 220 million but declining. Granted, the SEC doesn’t require public companies to divulge such details to the investment community, but for a company whose market cap has been buoyed by shareholder trust, Amazon’s opacity has been testing investor patience. Every quarter, buy- and sell-side analysts join in a conference call with Tom Szkutak, Amazon’s CFO, and pepper him with questions about company operations. But Szkutak doggedly dodges each query; as exemplified by his replies during Amazon’s Q4 2013 analyst call: “I am sorry I can’t help you … you have to wait on that … In terms of the details, I can’t really give you a lot of color … you will have to stay tuned on that one … I can’t talk to the specifics of that … there is not a lot I can help you with there … I wouldn’t speculate what we would do or not do going forward … I wouldn’t speculate. We might or might not do in the future … if you look back at what we have done, you can’t expect that we might do [it] going forward … I wouldn’t want to speculate what they would or wouldn’t do related to pricing … it’s hard to tell, honestly. It’s hard to know … it’s very early … that’s really all I can say … I can’t comment.” At Amazon, every obfuscating quarterly conference call feels like Groundhog Day. What’s Next for Amazon? So Amazon is arguably guilty as charged of disappointing earnings, worrisome increases in business complexity and investment, compounded by a stubborn unwillingness to share more information about business operations. The market has clearly lost confidence; Amazon is currently trading 25% off its 2014 peak. Does the current market sentiment signal the need for a fundamental shift in Amazon’s overarching business vision, strategy or priorities? I don’t think so. Taking the long view, it is somewhat puzzling that investors have seemingly become so unnerved by Amazon’s recent business performance. There is nothing particularly new or different in Amazon’s business priorities, or in its operating results through the first half of 2014. Jeff Bezos is managing Amazon today exactly as he said he would 17 years ago, making good on his longstanding commitment to prioritize long-term growth and market leadership over short-term financial returns. As such, it shouldn’t be surprising that Amazon has only beat quarterly earnings estimates half the time over the past 20 reporting quarters. So why have investors suddenly become impatient? Admittedly, there are some headwinds of concern. To begin with, Amazon’s recent EPS misses have come in bunches – viz. 4 out of the last 5 quarters. Then too, some of Amazon’s current business development priorities – cloud computing and original video content development — have particularly high investment thresholds with inherently long paybacks. More generally, the law of large numbers is catching up with Amazon, making the required size of its investment bets and risks higher. Finally, as Amazon has moved farther afield into new business ventures, it has attracted new and stronger competitors. For example, AWS, Amazon’s industry-leading cloud computing business, is encountering fierce price competition from deep pocketed, committed players such as IBM, Microsoft and Google. So it shouldn’t be surprising that Amazon’s historically thin profit margins are under additional pressure. But strategic, growth-oriented companies who are able and willing to sustain new business development activity through cyclical business swings are often rewarded over the long term. As a case in point, Amazon’s relentless focus on new business development and market leadership has propelled its unprecedented long-term growth. Lest there be any doubt that Jeff Bezos is continuing to manage for long-term growth, consider the comparative business performance between Amazon and two of its major competitors: Walmart, the largest global retailer and IBM, a technology leader and fast follower in cloud computing. Where Do The Profits Go? As illustrated below, Amazon performed reasonably well in generating cash from business operations in 2013: 7.4% of revenues compared to 4.9% and 17.5% for Walmart and IBM respectively. What really distinguishes these three large enterprises is how each chooses to deploy their capital. Amazon spends far more of its cash from operations on R&D and Capex – the engines of growth – than Walmart or IBM. The payoff is in topline growth: 23% for Amazon vs. low single digit or negative for its competitors. In contrast, Walmart and IBM reward their shareholders with near term gratification in the form of dividends and stock buybacks (29% and 73% of cash from operations in 2013 for Walmart and IBM respectively). To understand the reason for these stark differences, it is worth repeating Jeff Bezos’ prescient comments in his 1997 letter to shareholders: “We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions… Because of our emphasis on the long term, we may make decisions and weigh tradeoffs differently than some companies… We aren’t so bold as to claim that [we have] the “right” investment philosophy, but it’s ours, and we would be remiss if we weren’t clear in the approach we have taken and will continue to take.” Virtually every month, Amazon seems to announce yet another major new business venture. Recent examples include Amazon Fresh (groceries), Amazon Local (local services), Get It Now (same day delivery), Amazon Payments (online payments), streaming video and audio services, original content, Fire Smartphone, aggressive expansion in India, etc. Critics who have grown impatient with Amazon’s lack of profits may be underestimating the long gestation period required for new-to-world ventures to yield attractive returns. This was certainly the case with Amazon’s initial ecommerce business, and subsequent third party marketplaces and Kindle platform, which took as long as a decade to go from concept to profitable returns. This is not to suggest that Amazon hasn’t experienced its share of abject failures, including the following initiatives, which either were abandoned, written off or salvaged only via pricey, face-saving acquisitions:

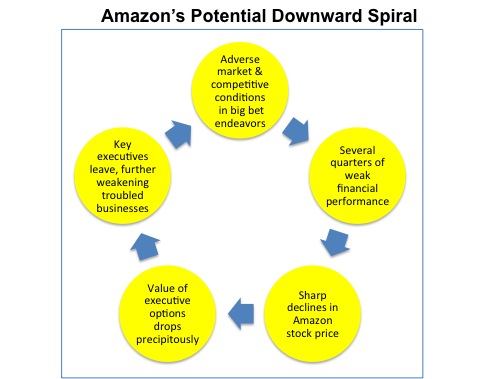

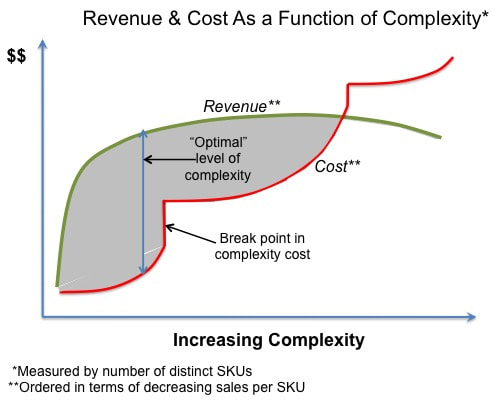

It is also important to recognize that Amazon’s preference for long-term growth over short-term profits is a matter of strategic choice. Amazon could easily boost its EPS by throttling back Capex and R&D investments (at the expense of growth), whereas, it is unclear whether Walmart or IBM are capable of turbocharging their topline growth. Investors who expect Amazon to deliberately scale back its growth initiatives and/or raise prices to achieve short-term profits either don’t understand the company or lack the appetite for Jeff Bezos’ long-term vision. Amazon is positioning itself at the epicenter of multiple businesses with exceptionally strong growth potential – global ecommerce, streaming media, electronic payments, cloud computing, same-day delivery services, the South-Asian continent etc. It is neither in Amazon’s DNA or long-term interest to slow its pursuit of these opportunities. What could go wrong? Is Amazon an indomitable force, bound for world domination? Of course not. There are a number of factors that could sidetrack Amazon’s prodigious appetite for growth and market leadership. The biggest challenge is management risk associated with the growing complexity of Amazon’s global business endeavors. As noted earlier, Amazon chooses to operate with razor thin margins across its business portfolio, and as such, will have to execute flawlessly to maintain torrid growth without jeopardizing their balance sheet. This will require a deep bench of committed executive talent across the enterprise. As their Q3 2014 guidance perhaps presages, Amazon may hit a bad patch if a few of its strategic growth initiatives take longer to materialize, attract more vigorous competition and/or require considerably higher investment than anticipated. Such outcomes, as noted below, could set in motion a downward spiral in business performance that might require significant retrenchment. Amazon relies heavily on options-based compensation in its senior executive ranks, making the company vulnerable to prolonged softness in the stock market. Given its dependence on public markets to fuel aggressive organic growth and acquisitions, Amazon’s reticence and repeated opacity in dealing with the investment community is another risk factor. A growing chorus of analysts and shareholders has lost patience with what they view as the company’s arrogant disregard of shareholders. True, the company can point to its unusual candor in initially articulating its management philosophy and to the shareholder-friendly returns achieved over the past decade (~500% stock price appreciation from mid-2004 to mid-2014). But the public has short a memory span, and Amazon risks needlessly squandering shareholder trust by doggedly refusing to respond to questions regarding business line results or to provide a credible case for the company’s path to profitability. Another risk factor of course is Jeff Bezos himself. Few companies are as personified by their CEO as Amazon. Bezos’s eventual successor will obviously have some very big shoes to fill, with outsized management transition risk. But for the foreseeable future, with respect to Jeff Bezos’ guiding vision, don’t expect new news from Amazon. If you’re looking for hints on Amazon’s strategic blueprint for the years ahead, look no further than Bezos’ 1997 letter to shareholders excerpted below.

1 Comment

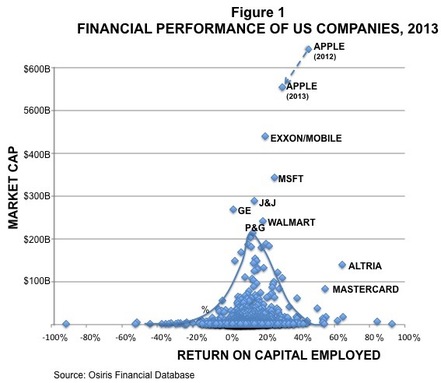

We’ve all been inspired by stories of brilliant entrepreneurs whose game-changing ideas sparked in humble settings — e.g. a garage (Steve Jobs), dorm room (Mark Zuckerberg) or Milanese coffee bar (Howard Schultz) — blossomed into market-leading global enterprises. A new generation of entrepreneurs is now building companies that reached $10 billion in market value in record time (Uber, Airbnb, WhatsApp), posing grave threats to established industries. It would appear that the traditional bases of competitive advantage that used to protect incumbent market leaders – scale, operational experience, brand image, customer base, distribution, and financial depth –- can no longer withstand the onslaught of upstart entrepreneurs. This was the theme of Malcolm Gladwell’s recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants. In his retelling of the biblical tale of David and Goliath, Gladwell portrays David as a fearless, agile and resourceful fighter who defeats the dim-witted, over-confident and ponderous oaf, Goliath. Gladwell rebuts the common belief that David was an underdog. In this mismatch – and in a surprisingly large number of others – Gladwell asserts that leaders have liabilities that make them particularly vulnerable to brash upstarts. This should come as no surprise to students of business. History is replete with examples of profitable, market-leading corporations who were felled by smaller but more nimble and effective competitors. For example, when AT&T — the largest company in the US for much of the 20th century– failed to adapt to deregulation and the emergence of wireless technologies, it was forced to sell its dwindling assets for a fraction of its historical peak value to one of its former regional divisions. AT&T’s vulnerability as a ponderous, customer-abusing monopoly was bitingly captured in one of Lily Tomlin’s signature parodies, with the tagline: “We don’t care. We don’t have to. We’re the phone company!” GM, which also held the distinction of being the largest US corporation for decades declared bankruptcy in 2009, and only lives on today (in shrunken form) as the beneficiary of a taxpayer bailout. But GM’s management shortcomings are no laughing matter, as details of its willful disregard of fatal vehicle design flaws have recently come to light. Kodak serves as yet another example of how the mighty have fallen. The firm, which enjoyed photographic film industry leadership for over a century, peaking at a 90+% market share in the mid-1970’s, declared bankruptcy in 2012. Kodak is a poster child of Clayton Christensen’sdisruptive technology theory, which explains why large enterprises struggle to adopt innovations such as digital imaging. Are these isolated examples of bad management bringing down venerable institutions, or are market-leading corporations destined to be felled by disruptive upstarts, by aggressive attacks from traditional competitors, or by a combination of both? Conventional wisdom has increasingly tilted toward the latter: market leaders cannot sustain global competitive advantage over the long term. Take Apple as a case in point. A gloomy outlook has been predicted for the post-Steve Jobs enterprise by no less than a Nobel Prize-winning economist (Paul Krugman), one of the most influential business theorists of the last 50 years[i] (Clayton Christensen), a Wall Street Journal reporter and best-selling author (Yukari Kane), an SAP board member writing for Der Spiegel (Stefan Schulz) and 71% of respondents to a recent Bloomberg global survey who say that Apple has lost its cachet as an industry innovator. The reasoning behind these arguments that the mighty must fall is not limited to Apple, but stem from a broader belief that large enterprises inevitably lose their competitive advantages over time. But this viewpoint is not only flawed, but perversely could become a self-fulfilling prophecy of corporate failure. If management truly believes that long-term above-market profitable growthis impossible, the logical response is to protect and harvest current assets and customers for as long as possible. But such an approach — playing not to lose, as opposed to playing to win – only serves to hasten the decline of incumbent market leaders. The biblical Goliath may have been a ponderous oaf, but large enterprise CEO’s don’t have to be. Business Goliaths can continue to prosper if they maintain the same entrepreneurial spirit and adaptability that led to their success in the first place. Let’s explore the case of Apple as a case in point. On September 29, 2012, Apple reported record earnings, capping a remarkable three-year run during which the company grew revenues by 266%, profits by 406% and market capitalization by 280%. Already the most highly valued company in the world, few expected that Apple could continue its torrid growth rate forever. But as Apple’s margins and growth rate did begin to abate over the ensuing 18 months, many pundits declared this was a broader sign of the company’s expected erosion of competitive advantage, dooming Apple to average financial performance – or worse – going forward. For example, one of my esteemed colleagues at Columbia Business School shared this provocative point of view with MBA students: It’s very hard to dominate big global markets. Nobody has ever dominated electronic devices. Trust me, we’ve seen it in related industries for Sony, for Motorola and for Nokia. They’ve had nothing like the margins of Apple, and the margins of Apple have gone down by at least a third in the last 16 to 18 months. You can’t dominate a big market… Apple is going straight down the tubes! — Bruce Greenwald, Columbia Business School Why would a company that has repeatedly demonstrated extraordinary customer insight, innovation, design expertise, marketing prowess, high quality manufacturing and retailing excellence be headed “straight down the tubes?” I believe there are three fallacious arguments that underscore the belief that Apple, and indeed all market leaders, eventually must lose their competitive advantage and above-market financial performance over time:

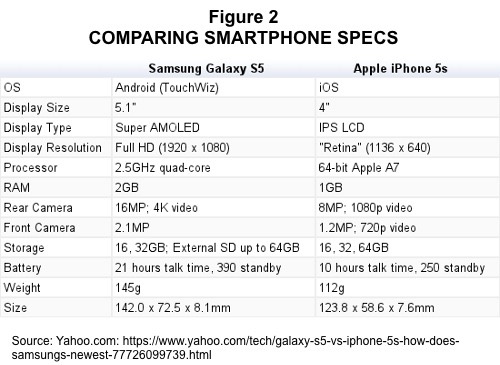

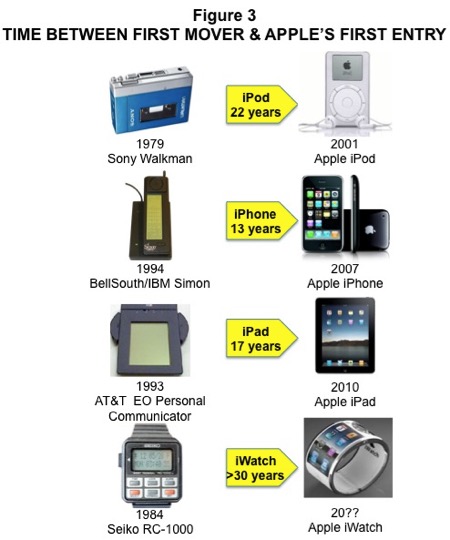

This law posits the obvious mathematical property that as a company grows, the incremental revenue required to maintain above market growth becomes ever larger. For Apple, whose revenue is currently $175 billion, the challenge is indeed daunting. For example, consider what would be required for Apple to grow it’s topline by 10% over the coming year, which while still above market average, is still only one-third of the compound annual growth rate the company achieved over the past five years. Growth of this magnitude would require the equivalent of adding the total revenue from companies such as Southwest Airlines or General Mills or US Steel to Apple’s current topline. No mean feat! Or think of it another way. Apple-watchers have been keenly anticipating the launch of theiWatch, in the intriguing “wearable technology” category. Characteristically, Apple has not been the first-mover in this emerging technology (nor was it in portable music players, smartphones or tablets), as smartwatches from Samsung, Pebble and more recently Google have been on the market for a year or more. But let’s give Apple the benefit of the doubt based on past success and assume that it achieves 10 times the industry sales of smartwatches achieved in 2013 ($712 million). At an assumed iWatch price of $299, this translates into annual sales of 24 million devices, generating just over $7 billion in revenue. As long as we’re being generous, let’s assume that each consumer also buys an average of $50 in apps each year for their slick new iWatch, of which Apple would claim a 30% revenue share. That would add a paltry $360 million in additional revenue (albeit at high margins). But the point here is that if Apple’s ability to continue to outgrow the market requires upwards of $17 billion of new revenue (and even more in the years ahead), it will take more than the vaunted iWatch to get the job done.[ii] It will undoubtedly be difficult for Apple to outgrow the market over the long term. But is it impossible? Absolutely not! The most definitive study on this issue was undertaken by the Corporate Executive Board in their landmark study of long-term growth rates. The CEB examined the performance of over 400 US companies that have been on the Fortune 100 list over the past 50 years, along with 90 non-US companies of a similar size. The authors concluded that approximately 13% of the nearly 500 large companies studied have been able to outgrow the market average for up to 50 years. So while outperforming the market over the long-term is a notably uncommon achievement, it is far from a mathematical impossibility. So where might Apple find its next growth wave, if not from the iWatch? There are several large opportunities that Apple may exploit that could fuel another round of dramatic growth. Opportunities include:

Under any circumstances, the assertion that Apple cannot continue to outperform the market because of the “law” of large numbers is pure sophistry – a case of simple mathematics posing as strategic thinking. The law of competition A second argument for why Apple is destined to decline falls under the rubric, the law of competition. According to this “law,” Apple’s historically sky-high returns on invested capital (ROIC) must inevitably revert to average levels for the following reasons.

Many industry observers have also pointed to the loss of technological leadership in the smartphone/tablet market, and the four-year lag since the company introduced its last game-changing product (iPad) as further evidence of Apple’s inability to maintain the competitive advantage required to sustain high margins (see Exhibit 2). But the inexorability of the law of competition applied to Apple and other highly profitable corporations is fundamentally flawed on two grounds:

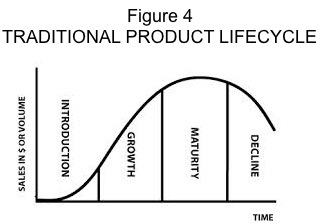

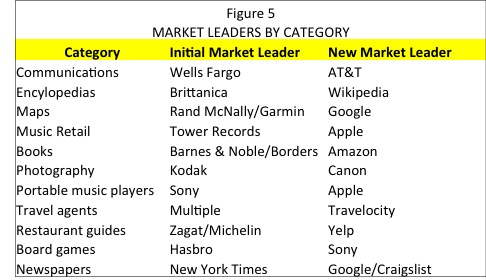

In fact, the [current smartwatches] do the opposite: they re-enforce all our old assumptions about the form, which is that you take your phone screen, make it small and stick it on your wrist. All I can think when I see them is: “Beam me up, Scotty!” And where’s the joy — or the desire — in that?… Admittedly, this has entirely to do with aesthetics, not functionality or engineering. But a smartwatch is an accessory, so aesthetics matters. Tech writers have been largely negative as well, noting the lack of useful functionality and confusing user interface of the current genre[iv]. Given these reviews, it’s not surprising that early sales in the smartwatch category have been disappointing. But if history repeats itself, Apple will once again set a new standard for style, form factor, capability, usability and market leadership when it launches its new iWatch, as rumored this fall. Critics who bemoan Apple’s late entry in this category as proof that Apple has lost its innovative edge in the post-Jobs era should remember that Apple’s unprecedented success with the iPod, iPhone and iPad came at least a decade after competitors pioneered product launches in these categories, as noted in Figure 3. The law of competitive advantage At the heart of the widespread conviction that large companies cannot sustain global leadership (marked by above-market growth and margins) is the underlying belief that the basis of a company’s competitive advantage inevitably erodes over time. A good starting point to examine the validity of this argument is to recall that all products and services experience aproduct life cycle. The familiar bell shaped curve shown in Figure 4 traces the trajectory of a new product through early adoption, rapid growth, maturity and eventual decline, driven by competitive technology advances and shifts in customer preferences. Schumpeter described this process as creative destruction over fifty years ago, and while the underlying dynamics are still compellingly true today, Downes and Nunes have argued that product life cycles have dramatically shortened due to a number of forces described in their recent book Big Bang Disruption[v]. Whatever one assumes about the duration of a product lifecycle – for example, in consumer electronics, successful products can come and go in less than a year – it is undeniably true that to sustain long-term market leadership, companies must consistently renew their product lineup with the “next new thing” in each of the categories in which they compete. This does not mean simply adding incremental improvements, which Christensen has noted propels most companies into a sustaining technology feature-function arms race. Rather, successful companies must rethink their consumer value proposition on an ongoing basis and be willing to consider entirely new product concepts aimed not only at current customers, but those poorly served by current offerings. And herein lies the challenge. In most cases, established market leaders struggle to disrupt themselves and eventually get overtaken by newcomers who bring radically different approaches to market that are often better and cheaper than existing products. The list of disruptive technology examples stretches back centuries and cuts across every industry sector. For example, as noted in Figure 5, Western Union’s telegraph business was decimated by Bell Telephone, which in turn gave way to Motorola/Nokia’s leadership in mobile handsets, which in turn got toppled by Apple/Samsung’s dominance of the smartphone market. Figure 5 lists numerous other cases where incumbent market leaders got toppled by newcomers who attacked with better product technology and/or superior business models. Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma explains that the reason why incumbents usually fail to disrupt themselves boils down to the strong tendency of large companies to:

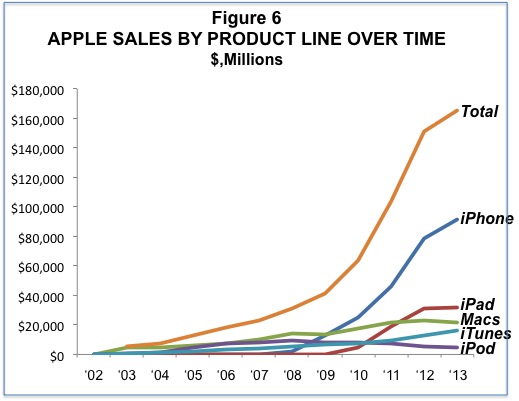

This is precisely what Apple and Amazon have done over the past 15 years. For example, Apple has continuously created new growth opportunities through breakthrough product innovation, sometimes at the expense of cannibalizing its existing products. This is illustrated in Figure 6 below, where the top line reflects the sum of sales from each of Apple’s main product lines over time. Similarly, Amazon’s exceptionally strong sustained topline growth (if not profitability) has been driven by relentless scope expansion and product innovation, often on initiatives with long-term payoffs and/or that have cannibalized existing product lines. Summing It Up The belief that business Goliaths will eventually lose their basis of competitive advantage stems from an implicit assumption that large enterprises suffer from strategic inertia. It is true that if a company (small or large) focuses more on defending current market positions than on renewing its basis of competitive advantage through meaningfully differentiated innovative new products and services, it will fail for all the reasons noted above:

Unlike scientific laws[vi], which describe intrinsic characteristics of our physical world, the business “laws” of large numbers, competition and competitive advantage can be broken by strong leadership. As Rita McGrath notes in her insightful book, Transient Advantage, winning companies can (and indeed must) repeatedly renew their basis of competitive advantage to sustain long-term profitable growth. It is admittedly not easy, and there are often strong headwinds that challenge corporate entrepreneurship. But exceptional CEO’s such as Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Howard Schultz (Starbucks), Marc Benioff (salesforce.com) and Fred Smith (FedEx) demonstrate that companies can continuously renew their bases of competitive advantage and achieve sustained profitable growth, notwithstanding the growing chorus of naysayers who assert that the mighty must fall. Whither Apple in the years ahead? Tim Cook’s leadership rather than immutable laws of large numbers, competition or competitive advantage will determine Apple’s business performance going forward. Time will tell. Intense media coverage of the standoff between Amazon and French publisher Hachette over ebook pricing has called into question who will control the future of the book industry. This debate has historical precedent. The invention that enabled the creation of the modern book publishing industry – the Gutenberg printing press – was ridiculed at its inception by the prior gatekeepers of the printed word. Monks who transcribed scriptures and religious writings by hand once controlled both the editorial and distribution functions in what was the parchment, if not the book industry. As with Hachette today, it is understandable that artisanal monks felt threatened by a new technology, which allowed laypersons to print and distribute any document at far lower cost. We have seen similar cases of technological disruption throughout history, be it combine harvesters and threshers that accelerated the agricultural revolution at the expense of family farmers, or Sam Walton’s big box retailing innovations that dislodged thousands of mom-and-pop retailers, or Internet news aggregators that are posing grave threats to today’s metro and national newspapers. In each of these transitions, critics – either businesses directly disrupted by new technologies or citizens wedded to traditional mores — have rightfully called attention to what is being lost in exchange for supposed progress. For example, some critics of inaugural telephone services feared that families would become asocial, no longer needing personal visits to communicate with friends and neighbors. One can only imagine how such luddites would feel today about text messaging and social networking! It is ultimately up to the consumer marketplace, moderated as necessary by regulators and the courts, to decide on the pace and direction of technological progress. Under any circumstances however, new technologies that undermine historical bases of competitive advantage are highly disruptive not only to the incumbents’ business economics, but to their emotional well-being as well. If one has spent an entire career mastering complex skills and business relationships only to find these assets diminishing in value, the impacts are viscerally disorienting and threatening. These dynamics are once again at play in the negotiations between Amazon and Hachette. But the roots of this dispute go much deeper than ebook pricing terms, and the stakes pose an existential threat for book publishers. The question is, what can publishers learn from history to guide the way forward? To understand this high stakes game, it’s important to start with the historical context underscoring the publishing industry’s dilemma and challenge. For starters, the book publishing industry was caught in a broken business model of their own making, long before Amazon introduced its first Kindle in 2007. Decades ago, publishers adopted an inherently costly business model whereby books were sold on consignment to bookstores. With thousands of releases each year added to an even larger backlist, it has always been extremely difficult to predict the popularity of any given new title. Either bookstores or publishers had to assume the risk of getting new titles on retailers’ shelves. With production economics favoring large print runs, publishers bit the bullet, allowing free returns from bookstores, and have lived with the costly consequences ever since: return rates averaging 40% across the industry. Facing chronic slow growth and anemic profitability, independent publishers were acquired by large media conglomerates (e.g. CBS, Bertelsmann, News Corporation), who by 2000 controlled over 80% of total book production. Backed by stronger balance sheets, book publishers increasingly focused their efforts on blockbuster hits, funneling multi-million dollar advances to established authors. But as competition drove up the bidding, publishers continued to struggle to earn attractive returns, typically losing money on over 70% of new releases. Moreover bigger bets on populist blockbusters meant fewer resources were available to support up-and-coming authors with advances, marketing, PR and promotions. Thus the industry’s storied past of cultivating great literature has been under pressure for decades, quite apart from the threat of ebooks or Amazon. To compound their woes, book publishers failed to anticipate and have been slow to effectively respond to the transformation of the publishing industry in the post-Kindle era. In November 2007, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos launched the original Kindle, surprising publishers with plans to price new ebook releases and best sellers at $9.99, well below the wholesale price publishers charged Amazon. With its aggressive, loss-leader pricing, wide selection and heavy marketing, ebook sales skyrocketed and Amazon’s market share reached nearly 90% within two years, alarming publishers. In response, in January, 2010, Hachette and four other publishers announced an agreement with Apple, whereby publishers would set retail prices for ebooks – typically 30% higher than Amazon’s prices at the time – giving retailers a fixed agency commission on each sale. But t he Department of Justice filed suit in April 2012, claiming Apple and the five publishers were guilty of collusive price-fixing. Hachette was one of three publishers that immediately chose to settle, restoring Amazon’s freedom to set ebook prices and agreeing to renewed negotiations after a two-year “cooling off” period, bringing us to today’s standoff between Amazon and Hachette. As digital penetration of the overall trade book industry approaches 50%, publisher profits have actually been strengthening, reflecting lower paper, print and binding costs and fewer unsold returns. But even if publishers temporarily succeed in maintaining their margins in the current round of negotiations, a far larger concern is the uncertain role legacy publishers will play, as printed books inevitably become an ancillary component to an ebook-dominated marketplace. The publishers’ longstanding source of market dominance has been their editorial gatekeeping function that historically dictated which books would be published at a scale requiring capital-intensive printing plants, and their distribution network that could rapidly place printed books on thousands of bookstore shelves. But with the advent of digital book production and distribution, these assets are no longer as valuable as they used to be, nor do they serve as effective barriers to competition. Thus, despite the recent tsunami of negative press being directed towards Amazon, this dispute is ultimately not about whether Amazon is a monopolist or monopsonist. Nor is it about whether Amazon is trying to use books as a loss leader to sell other merchandise or whether the company is treating Hachette, authors or its own customers fairly. It is also not about whether book publishers as currently configured are an essential bedrock of our society. It is about whether publishers can retool their business capabilities to maintain a vital role in adding value to all stakeholders in an industry where books will increasingly be produced, marketed, reviewed and sold in profoundly different ways. What does this mean in practical terms? Many authors who once would have been thrilled to be offered a legacy publisher contract are now asking: “what can you do for me that I can’t obtain elsewhere?” Publishers are quick to point out their longstanding editorial excellence, which will undoubtedly continue to be important. But to succeed in the post-digital era, publishers will also need to excel in customer relationship marketing, exploitation of social media, video production and promotion, multi-media web design and virtual book promotion as well as increasing the efficiency of their business operations and offering far more competitive digital book royalties. Right now, digital publishing capabilities are being driven and refined by a wide range of new competitors – native epublishers, enterprising self-published authors and a host of specialists providing a la carte services, including cover design and graphics, editing/copyediting, fact checking, videography, digital marketing, business analytics and market trend analysis. Publishers who continue to focus their attention and anger on Amazon rather than on the broader forces reshaping the book publishing industry are in grave danger of losing their battle for relevance and possibly survival. The imperative now is to build new skills necessary to survive and prosper in this rapidly changing industry. Publishers need to get beyond defending their nobility while demonizing Amazon, and start fighting more effectively on the new battlefield. As a fight over ebook pricing intensifies between French book publisher Hachette and online retailer Amazon (AMZN), some are suggesting that Amazon customers are being left behind. While details of the ongoing standoff are sketchy, it has become clear that Amazon is pressuring Hachette by making access to its books difficult on amazon.com. As an author whose recent book was published by Hachette, Fortune’s Adam Lashinsky penned an article earlier this week that takes issue with Amazon’s behavior as contrary to the company’s ostensible obsession with customer service. I would argue that he is confusing “anti-consumer” with “fierce competitor” in characterizing Amazon’s behavior. By way of background, this dispute dates back to November, 2007, when Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos launched the original Kindle, surprising publishers with plans to price new ebook releases and best sellers at $9.99, well below the wholesale price publishers charged Amazon. At the time, publishers charged Amazon and other retailers the same wholesale price for e-books as for hardcovers, typically around $13. With its aggressive, loss-leader pricing, wide selection and heavy marketing, ebook sales skyrocketed and Amazon’s market share reached nearly 90%, alarming publishers. In response, in January, 2010, Hachette and four other publishers announced an agreement with Apple (AAPL), whereby publishers would set retail prices for ebooks – typically 30% higher than Amazon’s prices at the time – giving retailers a fixed agency commission on each sale. The Department of Justice filed suit in April, 2012, claiming Apple and the five publishers were guilty of collusive price-fixing. Hachette was one of three publishers that chose to settle, providing Amazon and other retailers immediate discretion in ebook pricing and agreeing to renewed negotiations after a two-year “cooling off” period, which brings us to today’s riff between Amazon and Hatchette. In his piece, Lashinsky says: “But let’s get back to the customer. Assume for a moment that Hachette is the bad guy here, that the smallest of the major book publishers is making unreasonable demands on Amazon. (This seems unlikely, but bear with me.) Even if Hachette were behaving badly, I’m scratching my head trying to figure out in what strange universe Amazon believes that making it difficult for its customers to buy Hachette’s products is consistent with “customer obsession.” I’m trying to understand how Amazon thinks this will help it “earn and keep customer trust.” I would argue that it’s a mistake to assume there are good guys or bad guys here. I don’t begrudge either side for fighting hard for their own interests. So let’s just look at the impact on consumers if either side gets their way. Hachette might prevail because they have a 100% monopoly on all their titles, and are pushing Amazon very hard with the threat of not selling any of their books at lower wholesale prices. Essentially, Hacehtte’s position for now appears to be: “our way or nothing — if you want our books, here’s the price, period.” If Amazon backs down, they will have to maintain high retail prices to cover high wholesale prices. Keep in mind of course that the publishers set high wholesale prices for ebooks from day one and then illegally colluded with Apple and other publishers to keep ebook retail prices high in 2010. Lashinksy seem to ignore these facts in brandishing Amazon as the anti-consumer player in this dispute. Now if Amazon prevails – despite having the relatively weak bargaining position of controlling only 33% of total book sales – Hachette (and then presumably other publishers) will be forced to lower wholesale prices, which Amazon will likely pass along to consumers. Consumers would be the obvious beneficiaries here, as they are across every product category on amazon.com. Turning Lashinsky’s argument around, I’m trying to understand what strange universe he lives in to believe that consumers won’t come out ahead if Amazon wins this fight. Lashinsky may be conflating author interest with consumer interest, and I can understand his disappointment in being collateral damage in this fight. But as he notes, consumers have alternative choices to buy his book (as I already have). After the dust settles, if Amazon wins, he will wind up selling morebooks at lower retail prices and probably earn higher royalty payments. I think Lashinsky should redirect some of his wrath on Hachette, who, like other major publishers, pays only a 25% royalty rate on e=book sales, compared to 50% from native e-publishers like Open Road Media or 50%-70% from Amazon (depending on ebook price). Right now, publishers are squeezing authors and consumers pretty hard. But it’s just business. I don’t waste a lot of energy worrying whether publishers are anti-consumer. Having said that, I stick with my prediction that major publishers will not be able to win this fight. Amazon has consumers on their side. That’s the universe I live in. A number of news stories have recently surfaced on lapses in management judgment of the worst kind: errors of omission and commission that have led to needless deaths. After hearing about the duplicity, cover-ups and lack of oversight at General Motors and the US Veterans Administration, one is tempted to ask how the culture and management mindsets in these organizations evolved to tolerate such egregious behavior? And these are only the latest cases in a long history of corporate misdeeds — e.g. Enron, Lehman, Cendent, HealthSouth, WorldCom — that raise the related question: what were they thinking?! In retrospect, even in the worst cases of fraudulent or reckless behavior, it is probably fair to say that the men and women behaving badly didn’t join a company with the intent to brazenly break the law or endanger innocent lives. More likely, they felt intense pressure to meet performance expectations, in a corporate environment where the downside risks of underperforming were perceived as higher than the likelihood of penalties for inappropriate behaviors. In short, such individuals probably slid into an immoral quagmire with very bad outcomes, one misdeed at a time. Many companies react to the glare of bad publicity by blaming one or two “bad apples” as the cause of their fall from grace. But this explanation is superficial and often masks the root cause: the corporate culture that tolerates, if not fuels employee misdeeds. Can Culture Be Changed? To her credit, General Motors’ CEO Mary Barra has acknowledged shortcomings in GM’s management culture that contributed to its failure to identify a fatal ignition switch design defect. In her testimony before Congress last month, Barra threw the “old GM” under the proverbial bus, citing an historical management mindset which placed cost savings over corporate responsibility. Barra pledged that the “new GM” has already begun to purge the demons of the company’s ignominious past. Eric Shinseki, United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs since 2009 is said to have inherited a “culture of fear” at the Veteran’s Administration. At the VA, some management officials allegedly gamed the system to artificially inflate performance statistics, protected by a corporate Omertà, where potential whistleblowers feared the organization’s longstandinghistory of retaliation. Can such debilitating cultural environments be reformed? The answer is yes, and with deceptive ease under the right circumstances. Yet cultural transformation remains devilishly difficult, where more often, bandaid solutions fail to reverse longstanding incentives and protocols that have promoted (perhaps unwittingly) dysfunctional employee and management behaviors. Take Ford, for example. When William Clay Ford, the fourth-generation family member to run the company, remarkably volunteered to abdicate his position as CEO in 2006 at age 49, the company was in perilous condition. Ford was on the verge of bankruptcy, its product lines were stale and poorly received, its international operations were in shambles, and it suffered poor quality, high costs, lagging technology and unimaginative styling. Ford lost nearly $15 billion in William Clay Ford’s last two years as CEO. Much of the blame could be attributed to Ford’s toxic culture, characterized by fierce turf battles, lack of collaboration and severe fault intolerance, all of which contributed to an unwillingness for executives to acknowledge management challenges or to participate in joint problem-solving efforts. It was not uncommon for example for Ford executives to purposely design cars for their own region in ways that would make them unsuitable for sale in other regions, lest another executive benefit. Shortly after Alan Mullaly (formerly head of Boeing’s commercial airplane division) took over as Ford’s CEO, he started a campaign to reform Ford’s culture. Under the banner “One Ford,” Mullaly instituted weekly Business Plan Review meetings with his direct reports where each executive was expected to assess the status of programs under their watch. Many observers attribute the beginning of the turnaround of Ford’s culture and business fortunes to one such meeting, early in Mullaly’s tenure, when the then head of US automotive operations, Mark Fields gave one of Ford’s new car development programs a red flag, under a Red/Yellow/Green evaluation system Mullaly instituted for his management reviews. As the episode has been retold, Fields’ colleagues were shocked. No one had red flagged a major program to a Ford CEO before (in this case, related to a balky tail gate latch design). Mullaly broke the stunned silence by applauding Fields for his candor and asking whether there was anything the Ford organization as a whole could do to help. This is the deceptively simple side of culture change. At most other organizations, this type of exchange between two senior executives would hardly be worth mentioning. But at Ford, it signaled a sea change in how management would behave and communicate. Honesty was applauded. Collaboration was the new norm. Mullaly consistently reinforced his expectations for a more collaborative culture in every management forum, and further reinforced desired corporate values by changing Ford’s compensation incentives. Before Mullaly arrived, employee bonuses were based entirely on individual and division performance, unwittingly encouraging fierce rivalries between executives in “competing” units. Mullaly instituted new incentives, where individual bonuses were more heavily dependent on overall corporate performance. As a result, Mullaly’s mantra of “One Ford” took on real meaning where it counts most — in employees’ wallets. Over time, the revised management behaviors at the top level of the organization filtered down through the workforce, influencing decision-making at all levels of the organization. After eight years at the helm, Mullaly is leaving Ford in great shape. Ford earned over $42 billion in the last five years. Surging sales of Escape sport-utility vehicles, F-Series pickups and Fusion sedans drove Ford’s U.S. sales up 11 percent last year. In China, the world’s largest car market, Ford now outsells Toyota, and Ford has even begun to see sustained market share gains in its historically weak European business. And, as an enduring testament to the cultural transformation he engineered at Ford, on July 1, Mullaly will turn the CEO reins over to Mark Fields, the first executive to raise a red flag in a Ford performance review meeting. Leadership Styles Time will tell whether the Mary Barra’s “new General Motors” has indeed mended its ways, but the new CEO has a tough job ahead. For one thing, Barra is a 33-year veteran of the old GM, including leadership positions in engineering groups responsible for vehicle design. Barra is very much a creature of the old GM that she now disavows. Moreover, Barra’s ability to forcefully communicate her new vision has undoubtedly been reined in by legal advisors, defending against pending lawsuits and recall actions that may cost the company billions of dollars. At the very time the new CEO needs to communicate with laser-like clarity, and to move with speed and purpose in transforming GM’s hidebound culture, Barra has been deliberate, cautious and slow, prompting a bitingly savage Saturday Night Live parody. One early action Barra did take, was to appoint a new Vice President of Global Vehicle Safety with “responsibility for the safety development of GM vehicle systems, confirmation and validation of safety performance, as well as post-sale safety activities, including recalls.” While on the surface, this appears to be a positive step, it leaves unanswered fundamental questions about whether GM has really addressed its management shortcomings.

As Apple noted at the time, the vast majority of iPhone owners didn’t experience mobile phone reception problems, and for the few that did (allegedly related to how users held their phones) a simple fix was to use a protective rubber bumper which Apple subsequently provided to customers for free. Nonetheless, when news of Apple’s “Antennagate” first broke, Steve Jobs abruptly cancelled one of his rare family vacations and raced back from Hawaii to Apple headquarters to personally lead days of intense management reviews aimed at understanding underlying engineering design issues and determining Apple’s corporate response. Within a couple of weeks, Jobs conducted an extensive press briefing on the causes and cures for Apple’s phone design issues. Less than a month later, Jobs fired Apple’s Senior Vice President of Devices Hardware Engineering. No new organizational entities were created to ensure Apple’s product design integrity. Jobs responded to the product quality issue with speed, decisiveness and action. While it is admittedly unfair to directly compare Barra’s and Jobs’ responses to product design problems, given significant differences in context, the fact still remains that the breadth, speed and authenticity of a CEO’s response to ongoing challenges is perhaps the most significant determinant of an organization’s culture. As such, Steve Jobs clearly left his mark on Apple’s organization and Mary Barra’s leadership impact is still work in progress. What About Your Company? If you are concerned about the health of your company’s culture, there are four leadership essentials that need to be in place to achieve an effective transformation.

Leadership matters.  Companies who get scant attention in the marketplace despite strong products can probably relate to Rodney Dangerfield’s signature, if grammatically flawed lament: “I don’t get no respect.” Unable to attract adequate consumer attention for their branded products, such companies often turn to negative advertising, mocking competitors’ products — or even worse — their customers. That is, they try to level the playing field by smacking down others rather than building themselves up. Samsung provides a recent example of this approach. Three months prior to the US launch of Apple’s iPhone 5 (September 21, 2012), Samsung had launched its own top-of-the line smartphone, the Galaxy S3, which included numerous features that the iPhone 5 would lack. Yet most of the press buzz and customer interest remained focused on the breathlessly anticipated iPhone 5 sales launch. To dramatize this perceived injustice, Samsung ran this television spot in which a mob of faux sophisticate, Apple enthusiasts kill time while waiting for the Apple store opening by babbling platitudes about rumored iPhone 5 features. For example, one customer asks (with a look of bewildered awe): “I heard the connector is all digital! What does that even mean?” This is mockery in high art form! It’s hard to gauge the impact of an ad campaign, but Apple went on to an all-time smartphone sales record with the iPhone 5, so obviously Samsung didn’t deter too many Apple enthusiasts from buying the object of their desire. But Samsung Galaxy S3 sales were also reasonably strong and Samsung repeated the same advertising tactic in advance of Apple’s subsequent smartphone launch — the Apple 5s/5c — (preceded five months earlier by the Samsung Galaxy S4). Not to be outdone, Nokia responded to all the fuss with an ad promoting its Lumina smartphone, mocking customers for their fealty to either Apple or Samsung products. So what are we to make of ads which mock competitors’ customers? Do they work? And even if so, are there downsides? The short answer is, mockery is no substitute for the need to establish a company’s own brand persona, and mocking the very customers you hope to attract can be viewed as petulant and snarky, further eroding an already weak brand. It should be crystal clear what types of situations motivate such tactics. Advertising mockery is utilized by companies with weak sales positions and/or brand images, who find themselves way behind market leaders with little perceived prospect of making inroads with traditional and more genteel advertising messages. So the most benign view of such tactics is that they attempt to shake prospective customers out of their comfort zones to think about a challenger company’s products in a new light. Fair enough. The foundation of strong brands But how did the targets of such advertising campaigns achieve their strong brand images in the first place? Successful brands are built on three foundations:

The corollary of course is that in order to maintain a strong brand, companies need to meet or exceed established expectations with each new product release. In this regard, Apple would be foolhardy to rush a new product to market just to incorporate a new feature or tool, without taking the time to refine the overall design, UI, build quality and performance to expected high standards. Apple has made and kept its brand promise of refined innovation to consumers over multiple generations of new products — the legacy of Steve Jobs. Strong brands also convey mutual trust. Loyal customers trust their preferred company to consistently deliver appealing products, while the company trusts the that its targeted customers will remain loyal as long as their needs are well met. Are there technophiles or early adopters that may abandon a current product the instant a new feature is offered by a competitor? Sure, but these customers are inherently disloyal to any brand and not worthy of a company’s pursuit, particularly if it means breaking the brand promise to core customers. If assiduously maintained, the mutual trust between a customer and her preferred brand is difficult for competitors to dislodge. Finally, strong brands provide comfort to consumers in reinforcing their symbolic identity, signaling membership in a desired social grouping. For example, it’s hard to imagine a bunch of hard-drinking, über football fan guys gathering around a big screen TV on a Sunday afternoon pounding down Amstel Light® beers with Kashi® Granola & Flax Seed Bars. Wrong symbolic identity for this gang! Any advertisement that makes heavy use of lifestyle images– and there are tons — is making a play to reach customers through symbolic identity. Product placement on popular TV shows is another technique towards this end. Luxury brands have long thrived on symbolic identity to exploit some consumers’ high willingness to pay for premium branded products that showcase their taste and wealth. Would a satisfied Luis Vuitton customer jump ship to a new brand which promised to deliver a stronger handbag zipper design? Unlikely. Relatedly, strong brands evoke strong emotional associations and imagery. For example, when I asked my MBA students to explain why they preferred their favorite brands, the answers were often grounded in highly emotive reactions. Some students were “inspired” by what Dove or Nike products stood for. Another admired Luis Vuitton for its ability to “deliver a transporting emotional experience.” And yet another relished Dunkin’ Donuts for providing “the same kiddy excitement whenever I grab a cup!” Thus strong brands impose high emotive switching costs. Challenger brands need to instill their own promise, sense of symbolic identity and mutual trust to dislodge brand leaders. At best, negative ads may be necessary, but they are definitely not sufficient for a weak challenger to build their own strong brand. Case in point: Subaru’s brand rebirth Subaru is a company on a roll. US sales in 2013 were well over 400,000 vehicles, setting a fifth straight annual sales record. Consumer Reports recently named Subaru the second best brand in the US (just behind Lexus), and the company confidently promoted its vehicles under the tag lines: “Confidence in Motion” and “Love: It’s What Make’s a Subaru a Subaru!” But it wasn’t always this way. In 1991 Subaru of America was on the ropes, with an operating income margin of negative 25% on sales of ~$1 billion. Their cars lagged far behind Toyota and Honda in brand strength, sales and price realization. With bankruptcy looming, Subaru’s ad agency, Wieden & Kennedy — best known for its Nike account — recommended that Subaru get snarky in negative ads against its stronger rivals. Subaru’s early-1990’s ad campaign openly mocked customers of its stronger rivals. One ad opened with the admonition: “A car is a car; it won’t make you handsomer or prettier and if it improves your standing with the neighbors, then you live amongst snobs.” A second ad, mockingly asserted that “a luxury car says a lot about its owner,” followed by head shots of officious-looking customers intoning what their car means to them, e.g.:

What’s ironic is that Subaru actually did have a highly distinctive product line — or at least half of their cars fit this description. Specifically, Subaru was one of only two companies (Audi was the other) that sold all-wheel drive (AWD) cars at the time. These vehicles delivered superior traction and handling, particularly in adverse weather conditions, and served as a source of highly tangible competitive differentiation from mainstream market offerings. But rather than make its AWD product distinctiveness the centerpiece of its brand “promise,” Subaru heavily promoted its less expensive front-wheel drive models which competed head-to-head with Toyota and Honda at a considerable disadvantage. Subaru’s mocking negative ad campaign only made a bad situation worse. Saving Subaru How did Subaru go from the brink of bankruptcy to becoming the fastest growing car company in the US? They completely redefined their brand around a highly differentiated, compelling consumer value proposition, and supported the repositioning with a credible, appealing marketing campaign that created a strong symbolic identity for a growing segment of customers. Here how:

Ironically, with their ill-considered mocking ad campaigns long behind them, Subaru returned to negative advertising in a 2011 with their humorous “Mediocrity” spots. In this campaign (thinly disguised as directed against Korean car company competition), ad spokespeople promote the faux benefits of a blandly styled, taupe-colored fictitious sedan called the “Mediocrity.” In one ad, a bland looking mother in a taupe blouse seated in front of her taupe Mediocrity says: “we’ve got two kids and a dog, so the last thing my family needs is more excitement when we drive!” In the same ad, a bland looking spokesman (in a taupe suit of course) pulls a sheet off a new taupe Mediocrity, intoning: “Introducing the 2011 Mediocrity; a car so basic, so understated, you’ll never have to worry about your blood circulating too quickly.” The difference between Subaru’s negative ads of the early 1990’s and the reprise twenty years later is in tone and intent. The snarky and derisive “A Car is Just A Car” campaign attempted to tear down the legitimacy of stronger competitors at a time when Subaru didn’t think it had much positive to say about itself. In contrast, the “Mediocrity” campaign used light-hearted humor to reinforce Subaru’s brand distinctiveness against less differentiated competitors. The first ad campaign made you wince; the latter induced chuckles.  Even Apple has played the game It’s interesting to note that one of the most extensive negative ad campaign ever was run by a company with perhaps the strongest brand image in the world. Between 2006 and 2009, Apple ran 66 TV spots under the banner “Get a Mac”. In these ads, a hip-looking young man assumes the role of a McIntosh computer in repartee with a pudgy, nerdy-looking guy symbolizing a Windows PC. With quips, barbs, sight gags, and one-liners, the PC is repeatedly portrayed as inferior to the Mac, but the PC-guy gets most of the joke lines, and viewers are led to feel more sympathy than pity for the PC guy. Apple used jocularity, not derision to make its points. Throughout this period, Apple’s US personal computer market share remained mired around 7.5%.

So do negative ads which poke fun at competitors’ customers work?

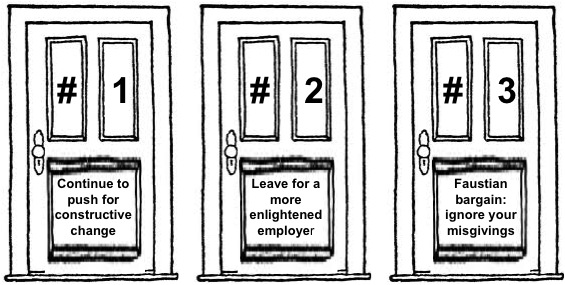

A recurring theme in my MBA course on business strategy this semester was courage. Executives need courage to create breakaway products that offer consumers a compelling value proposition in ways that are meaningfully different from competition. Such executives are not afraid to break from competitive norms; to go beyond the safe boundaries of incremental improvements. Think Tesla, Post-It Notes, Swiffer and Ikea. And executives also need courage to go all-in in ensuring that the company’s resources, assets and management incentives are fully aligned to support the breakaway strategy. Such executives become personally vested in, and identified with their business strategy, earning justified glory or job-ending rebuke, depending on outcomes. Think Nicolas Hayek at Swatch, Steve Jobs (second time around) at Apple and Dave Barger at jetBlue. The products and executives cited above provide inspirational stories of creative leadership, driven by leaders who live by the credo of “no guts, no glory.” But what are the implications for MBA graduates most of whom are about to enter the corporate workforce in entry level positions? They are not initially in a position to exert courageous leadership. Or are they? A guest speaker in my class near the end of the semester — entrepreneur, author, blogger Seth Godin — urged my students to approach their first (and every) job with the mindset to “make a ruckus” and “don’t be afraid to be fired.” In short, Godin was rendering themes from my course in very personal terms. Customer centricity and playing to win (as opposed to playing not to lose) are not just mantras for corporate leaders, but a code for all to live by. Now it’s easy for financially secure elders like Godin and myself to proselytize a message of personal leadership, driven by the principles of effective strategy without fear of rocking the boat. But what if you’re just feeling your way around a new job in a new company whose paycheck is critical to repairing your post-MBA balance sheet? How and where do you draw the line between pushing for constructive change and being a good team player in supporting your company’s current business direction? My short answer is there is no hard line, it’s a decidedly personal decision, but nevercompromise being honest with yourself about what you’re doing and why. It’s quite natural for students to approach their first post-MBA job with a combination of optimism and excitement. But once on board, what would you do if you find yourself becoming concerned and ultimately convinced that your company is headed in the wrong direction? You have three choices:

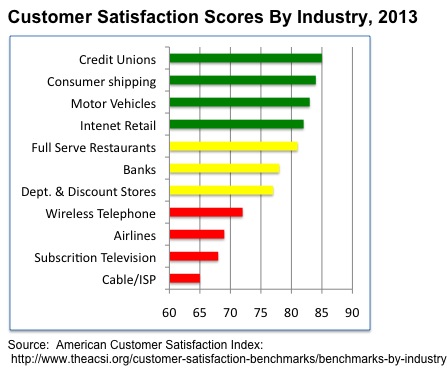

Here’s a hypothetical example to put this question to the test. Suppose you accept the premise that strategy should be formulated from an “outside-in” perspective — that is, the highest priority being to create and consistently deliver a compelling consumer value proposition. Internal capabilities, incentives and corporate policies should be aligned and managed towards supporting this end. That all sounds reasonable enough, but the reality is that companies vary widely in their commitment to operate in such a fashion. Watch what companies do, not what they say. Every company says that they value their customers, but there is a wide variance in perceived customer satisfaction across industries to suggest otherwise. For example, the exhibit below displays 2013 results from ACSI, a spinout from the University of Michigan, on customer satisfaction by industry on a 0-100 index scale. You probably shouldn’t be surprised to see that companies in the red zone — broadband/ISPs (e.g. Comcast), subscription television (e.g. Time Warner), airlines (e.g. United) and wireless telephone providers (e.g. AT&T Mobility) score quite poorly in delivering an appealing customer experience. There are a few bright spots (e.g. jetBlue), but by and large, companies in these industries have knowingly implemented business practices that extract revenue in ways that aggravate their customers. Now suppose you were hired in as a freshly minted MBA to manage Policy Assessment and Strategy for the Customer Service Group of one of the lower performing companies in one of these industries. After a few months into the job, with due diligence under your belt from proprietary company surveys, auditing customer service calls and internal management interviews, you report your initial findings to your boss. For starters, you confidently summarize what you believe to be the root causes of your company’s chronically poor customer satisfaction performance: