|

On March 1, a prestigious MIT research center published a Research Brief on a study of rideshare driver compensation, led by a respected Stanford University researcher. The MIT report asserted that half of Uber and Lyft drivers earn no more than $3.37 per hour, after accounting for vehicle ownership and operating costs. The study further concluded that 74% of rideshare drivers earn less than the minimum wage in their state, 30% are actually losing money and 74% of whatever driver profits there are could go untaxed, if drivers claim the standard IRS deduction for vehicle operating costs. After MIT published its Research Brief, the press was quick to pounce, with brutal, indignation-laden headlines:

Ordinarily, this story would end here, with little additional fanfare. Stephen Zoepf isn’t the first university researcher to make an error in publishing preliminary sponsored research findings, and to his credit, Zoepf promptly issued a retraction, if not an apology, after being advised of his mistake. But this story shouldn’t end here as it provides a useful parable on the powerful forces that promote the creation and viral dissemination of inaccurate information, aka fake news. The insidious dynamics behind this saga need to be told in three parts.

The mistake in the MIT Research Brief can be traced to how MIT researchers improperly interpreted responses from 1,121 Uber and Lyft drivers surveyed in January, 2017. In explaining his faux pas, the MIT team lead benignly states, “I can see how the question on revenue might have been interpreted differently by respondents.” But when over 1,000 respondents interpret a survey question one way, and an experienced MIT research team sees the survey responses in an entirely different light, there has to be a reason. It’s fair to assume that Uber and Lyft respondents answered the critical survey question driving MIT’s analysis of driver earnings as it was originally posed:“How much money do you make in the average month? Combine the income from all your on-demand activities.” But the MIT study team inexplicably changed the wording and hence the meaning of this key survey question in their analysis. In their full study report, the MIT researchers state: “Responses to Question 14 ‘How much money do you make in the average month?’ determined monthly revenue for each driver.” By dropping the second part of Question 14, clarifying its reference to only earnings from on-demand activities, the MIT researchers erroneously were led to reduce driver earnings for the 83% of respondents who reported having other sources of income. As a result, MIT’s calculations of gross and net driver earnings were understated by more than a factor of two. In response to my email to the lead study author, which mirrored Uber’s critique of MIT's study methodology, Stephen Zoepf told me “I’m re-running the analysis this weekend using Uber’s more optimistic assumptions.” But I don’t see this as a case of being more or less optimistic, but simply being accurate, consistent and applying common sense in conducting research to high academic standards. My bigger concern with this research project – its epic fail – was the failure to recognize obvious red flags or to vet the results with knowledgeable professionals who could have quickly identified methodological errors, prior to publication. But instead, the project team charged ahead to publish its preliminary research findings, ignoring:

The Role of the Press There are immense pressures on news organizations to avoid getting left behind in reporting breaking news, and this story offered the promise of immense “eye candy” appeal. After all, the study came from a highly trusted source, and presented alarmingly negative findings on a widely known and frequently maligned company. Shortly after the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Research (CEEPR) published its Research Brief, the story went viral, precipitating a newsroom arms race to get the shockingly low estimates of rideshare driver earnings out to the public. When I last checked, a Google search on “MIT study Uber driver earnings” generated over 700,000 search results, undoubtedly exposing the bogus study results to tens of millions of viewers. It was naïve for the study authors and its sponsor to not recognize the dangers of publishing such a potentially explosive and unvetted study as a working draft to solicit feedback on the approach and findings. The press predictably treated the results as gospel (without the benefit of reading the full report), and broadly condemned Uber’s (and Lyft’s) perceived abusive business practices. Some news organizations did publish a brief follow-up on Uber’s rebuttal and the MIT team leader’s ensuing retraction, but with far lower impact and reader interest. The damage was done. Uber’ Public Relations Hell The public relations harm to Uber as a result of MIT’s initial study release is self evident. But even with Uber’s prompt rebuttal and the study author’s retraction, Uber’s reputation is bound to suffer in the weeks ahead. One widely read business publication jumped on the initial release of the MIT study findings by headlining: “Uber’s New CEO Faces New PR Disaster.” But when Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi tweeted a testy rejection of the flawed MIT study results, the same publication followed with the story: “With a Single, Insulting Tweet, Uber's CEO Just Destroyed Months of Hard Work.” Opprobrium throughout the news cycle on this story has fallen mostly on Uber, rather than on the instigators of this bogus news firestorm. Stephen Zoepf’s revised study results are continuing to create negative press for Uber. For example, NPR recently reported that “in each new calculation method a significant percentage of drivers are still earning less than minimum wage in their state — 54 percent in the first case or 41 percent in the second case, according to Zoepf.” While this statement is factually accurate, it fails to characterize MIT's research findings in proper context. Gig economy jobs provide considerable flexibility that is highly valued by drivers. Comparing Uber and Lyft driver compensation to minimum wage rates is mixing apples and oranges: part time/flexible work vs. full time/inflexible employment. The MIT study correctly observed that fewer than 20% of drivers rely exclusively on ridesharing services for their earned income. For most drivers, ridesharing is hard work that doesn't pay particularly well, resulting in extremely high turnover rates. On the other hand, for many drivers, ridesharing provides a valued supplement to household income with considerable scheduling flexibility and frictionless entry/exit. The value drivers associate with flexible, part time scheduling helps explain why less than one-third of rideshare drivers are dissatisfied with their work experience with Uber and Lyft, despite seemingly low hourly pay. The market will ultimately decide whether rideshare driver earnings are adequate to fuel Uber and Lyft's profit and growth aspirations. Time will tell. In the meantime, when MIT releases its revised full study report, it would be helpful for the authors to present a balanced, context-sensitive view on driver earnings that hopefully can be accurately reported by the press. Lessons Learned There are no singular villains or heroes in this story. The creators, disseminators and avid news readers drawn to the flawed MIT study each had reasons to behave as they did. Guarding against the epidemic of fake news that surrounds us will require all stakeholders to exercise better judgment in avoiding the fool’s race to spread and consume news with more shock value than validity.

Disclaimers:

0 Comments

As 2017 drew to a close, Uber secured another round of investment to shore up its dwindling balance sheet. Softbank’s tender offer injected $1.25 billion of fresh capital into the company, while giving seed investors who chose to cash out a whopping 360,000% return on their investment. Softbank’s CEO, Masayoshi Son has made a fortune from his prior big bets on Yahoo, Vodafone, Alibaba, Sprint, Nvidia and others. What is Son seeing in Uber (or, for that matter in other ride sharing companies Didi Chuxing, Ola, Grab and 99, in which Softbank has also heavily invested) that overlooks the company’s dismal financial performance to date?

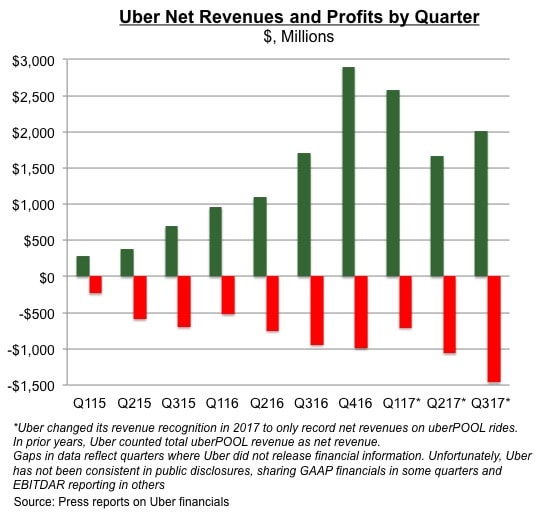

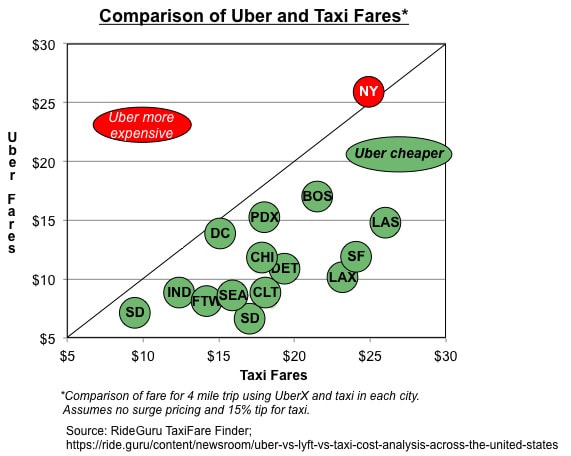

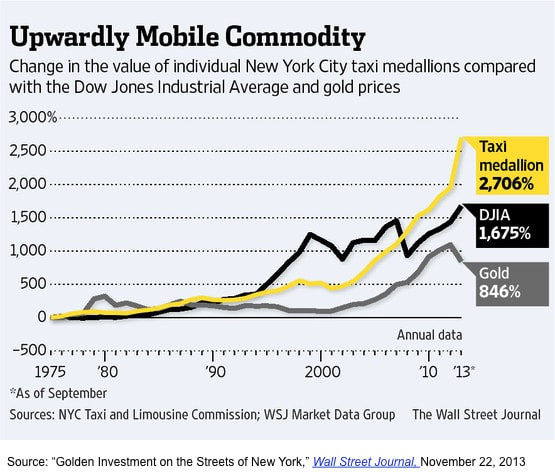

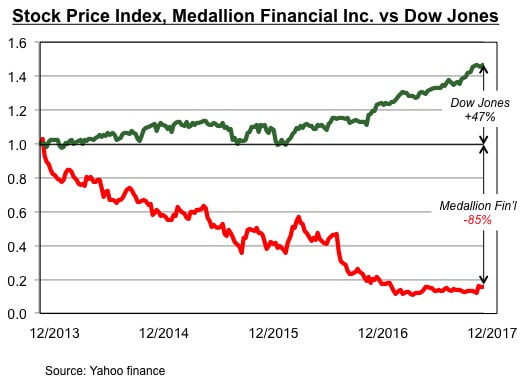

My Forbes article last month, “Why Can’t Uber Make Money?,” identified fundamental weaknesses in Uber’s business model that has led the company to lose more money, faster than any startup enterprise in history. In the year just ended—Uber’s seventh—the company’s projected loss of $5 billion is unprecedented and clearly unsustainable. And there is little reason to believe that on its current course, Uber can stop the bleeding any time soon for one simple reason: a fundamentally broken business model. The taxi industry that Uber is seeking to disrupt was never particularly profitable when allowed to expand in unregulated markets, reflecting the industry’s low barriers to entry, high variable costs, low economies of scale and intense price competition—and Uber’s current business model doesn’t fundamentally change these structural industry characteristics. While Uber’s business model has created enormous value for consumers, propelling the company’s rapid growth, its extremely aggressive pricing simply doesn’t generate enough revenue to deliver attractive compensation to drivers and sizable profits to shareholders. By pricing its services roughly 30% below comparable taxi fares and then retaining 25% or more of gross bookings for itself, Uber has squeezed the revenues available to compensate drivers, who are ultimately responsible for providing the labor, equipment, maintenance, insurance and fuel to serve consumers. There is little in Uber’s current business model that promises to reduce the factor costs of its ridesharing service, nor are there inherent economies of scale that would lower unit operating costs with continued growth. Thus, in attempting to disrupt the taxi industry, Uber has shifted, but not significantly reduced the costs of delivering an inherently low profit service. The same value trap–low consumer willingness to pay, high unit costs and low economies of scale—also saps the profit potential from “last-mile” delivery services like uberEATS and uber RUSH who compete against a host of money-losing competitors like Postmates, Doordash and Instacart. Investors poured more than $9 billion into 125 on-demand delivery companies over the past decade in search of the next “Uber for X” unicorn, but new capital is drying up, as many venture capitalists are losing money and faith in a sector with bankruptcies and fire sales piling up. For example, within the last two years, Doordash was forced to accept a 16% valuation down round (with harsh terms to boot) while other urban delivery players like SpoonRocket, Sprig and Maple shuttered operations. Contrast these challenging economics with other startup enterprises that are creating and capturing value by disrupting industries with historically high margins andhigh costs. In such cases—eyewear, fashion apparel, mattresses and enterprise business systems—companies like Warby Parker, Rent The Runway, Casper and Amazon AWS have developed innovative business models delivering better service at considerably lower cost across the value chain, which fundamentally alters industry economics. For example, Warby Parker and Casper disintermediated inefficient industry value chains with as high as a 10-fold markup from manufacturing cost to retail price in their respective industries, to deliver superior customer experiences at vastly lower prices than traditional competitors, while still leaving room for sustainable operating margins. Such is not the case with Uber. Since the dawn of the internet, we’ve witnessed many sobering cases of companies with intriguing value propositions but unproven business models who flamed out in their mad dash to scale fast, profit later. Kozmo and Urbanfetch were early casualties in the urban last-mile delivery business, burning through more than $300 million of venture capital before declaring bankruptcy in 2001. That same year also claimed another epic business model meltdown–Webvan, the company that pioneered the online grocery delivery category. Flush with $800 million in venture and IPO capital raised during the height of the eCommerce bubble, Webvan raced to establish first mover advantage, building highly automated pick-and-pack warehouses in 26 cities across the US. But Webvan never got a chance to master the executional discipline required to operate profitably in the low-margin grocery category, and each new launch city merely deepened their negative cash flow. As a result, Webvan went from IPO to bankruptcy in only 18 months, one of the fastest public company flameouts in history. The Webvan saga presents a cautionary tale for any company engaged in a mad dash to scale fast and profit later, particularly in categories with challenging underlying economics. To be sure, Uber has several benefits that its predecessors lacked at the turn of the new Millennium, including low cost computing, bandwidth, GPS, mapping and software tools, widespread consumer acceptance of mobile and online transactions, and deeper (albeit dwindling) capital reserves. Nonetheless, like Webvan, Uber has yet to prove it can consistently operate profitably in major metro markets, despite seven years of effort, yielding more than $9 billion of negative cash flow. Against this backdrop, what does Masayoshi Son see in Uber that warrants its recently completed $7.7 billion investment for a 15% stake in the company? The answer likely lies in Son’s expectation for improved financial performance over two distinct time horizons. In the short- to medium-term, while Uber can no longer realistically expect to become the “last man standing” in major metro markets around the world, it can still hope that a reduced set of large ridesharing competitors will become more disciplined in avoiding financially ruinous fare wars, much as US airlines did in reversing thirty years of shareholder value destruction by undertaking industry-consolidating acquisitions over the past decade. If and when competition in the ridesharing and last-mile delivery sectors does thin out (despite relatively low barriers to entry), remaining players could enjoy somewhat greater pricing power and decreased driver recruiting costs. Softbank also has invested heavily in other major ridesharing companies, which should promote more favorable coopetition between Uber and Didi Chuxing, Ola, Grab and 99 in global markets. Nonetheless, the ridesharing industry has dug itself into a deep hole, and underlying business model weaknesses are unlikely to radically improve the industry’s profit outlook. Over the longer term, Uber has always pinned its potential for improved financial performance on autonomous vehicles (cars and air taxi drones), taking expensive and unreliable drivers out of the equation. In theory, driverless vehicles should allow ridesharing providers to increase productivity and service quality while sharply reducing operating cost -- subject to three critical caveats. First, the economics of autonomous vehicle technology have yet to be proven, and we don’t yet fully understand the tradeoffs associated with substituting capital for labor in transforming the industry. Under any circumstances, widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles will eventually require billions of dollars of new investment, which Uber may not be in a position to fund. Second, Uber is far from alone in the race to perfect driverless vehicles, and it is yet unclear whether Google (Waymo), the car industry or rideshare companies will be best positioned to extract value from deploying driverless vehicles to ridesharing services. If the key to sustainable profitability in the urban transport sector is driven primarily by access to superior autonomous vehicle technology (with high barriers to entry), and not in operating a metro-by-metro ridesharing platforms (with relatively low barriers to entry), driverless vehicles may not prove to be the salvation to Uber’s elusive quest for profitability. Finally, under the best of circumstances, the time framefor widespread deployment of “Level 5” autonomous vehicles in dense urban areas is likely to be measured in decades, not years. This is not a bet that any investor looking for a quick return on investment is likely to make. And this reality may ultimately explain Masayoshi Son’s big bet on Uber et al, to become the kingmaker of the ridesharing industry. Son has consistently proven himself to be an exceptionally patient visionary, willing to make large investments in nascent technologies that have yielded outsized returns over time. Son has been an early and big player and ultimate winner in the explosive growth of Internet 1.0 (Yahoo), eCommerce (Alibaba), telecommunications (Vodafone, Sprint), microprocessing (ARM, Nvidia), robotics (iRobot, Boston Dynamics), the sharing economy (WeWork), and solar energy (SBG Cleantech). Time will tell if Son’s bet on ridesharing will also pay off. But in order to survive until the hoped for transition to a more profitable driverless vehicle future, Uber will need to take aggressive near-term actions to improve operating performance. Two imperatives should be high on Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi’s priority list: 1. Fix driver relations. In Uber’s two-sided market, it is critical to effectively balance the economics and participant experience of both riders and drivers. Uber has consistently put rider satisfaction ahead of its treatment and compensation of drivers. This bias has led to low driver satisfaction and growing turnover, both in absolute terms and relative to its main US competitor, Lyft. Recent corrective efforts have been a step in the right direction, but still gallingly inadequate, as exemplified by the (deliberately?) poor execution of long-overdue in-app tipping, and the company’s strategically sound, but poorly communicated upfront pricing initiative. Trying to run a service business with competitively disadvantaged satisfaction of mission critical de facto employees is an expensive and losing hand. Khosrowshahi would be well advised to add an additional item to his recently promulgated statement of Uber Cultural Norms that commits the company to ensuring and delivering the most rewarding and supportive driver experience in the industry. This will undoubtedly be a costly transition, which only reaffirms the strategic imperative of focusing on selected markets where Uber can sustain competitively advantaged pricing power and operational efficiency. 2. Shrink to grow. From its inception, Uber made a calculated bet that it could achieve global domination, wiping out both incumbent taxi companies and competing shared ride providers, to enable the company to exercise monopoly pricing power. But it is now apparent that Uber has lost this bet in its headlong rush into an industry with historically low profit potential and low barriers to entry. There are undoubtedly defensible geographic markets and user segments in the global ridesharing market that can currently sustain profitable operations. Khosrowshahi will need some serious soul-searching to rethink Uber’s soaring ambition and penchant to win-at-all-costs in all markets. This will require abandoning current operations showing little potential for near-term profitability, while continuing to explore opportunities to exploit industry-leading scale in selected markets that promote competitively advantaged operations (e.g. uberPOOL and Express POOL which can yield lower costs, higher asset productivity and greater returns, particularly for market share leaders). There are numerous inspiring case studies of overextended companies that retrenched to a defensible core, only to reemerge down the road, stronger than ever. Given Uber’s current burn rate, Uber clearly needs to zero base budget its sprawling current operations to decide where to defend the core at all costs, and where the company should temporarily retreat to live to fight another day. Softbank has given Uber additional runway to get its operations and finances under control. But the company will have to make some hard choices to ensure that unlike Webvan, its soaring ambitions don’t result in a mad dash to oblivion. By any measure, Uber’s seven-year entrepreneurial journey has been extraordinary. No venture has ever raised more capital, grown as fast, operated more globally, reached as lofty a valuation -- or lost as much money as Uber. Last month, Uber reported a third-quarter loss of nearly $1.5 billion, bringing its 2017 year-to-date red ink to $3.2 billion. Losses of this magnitude are clearly not sustainable, and call for an explanation of why Uber has been unable to rein in ballooning costs and what it will need to do to survive, let alone prosper. Much of the recent discourse on Uber has focused on the numerous unethical and possibly illegal corporate behaviors that continue to dog the company, six months after founder Travis Kalanick resigned as CEO. But while the reputational damage from Kalanick’s win-at-all-costs ethos has certainly not helped Uber’s cause, it has masked a far deeper problem facing the company. Uber’s elephant in the room is that its business model is fundamentally broken. To understand why, it is useful to assess Uber’s business model in the context of the history of the taxi industry. Shortly after launching an app-hailing black car limo service in San Francisco in 2010, Uber founders Garrett Camp and Travis Kalanick recognized the potential to disrupt the $100 billion global taxi industry. After all, this heavily regulated sector had seen little innovation over the prior century, leaving customers to cope with an expensive, inconvenient service that rarely seemed available when most needed. Enter Uber, who incorporated widely available technologies – GPS, Google Maps and mobile computing – into a well-designed app to create a customer pleasing, smartphone-enabled urban transportation service. Not only did Uber offer enhanced urban mobility, but it was usually cheaper and more convenient than taxis as well. Ride hailing and payment processing were fully automated and Uber was priced well below (30% or more) comparable taxi services. With better/faster/cheaper service, Uber became an immediate hit with consumers, emboldening the company to expand rapidly. To recruit drivers in Uber’s two-sided market, Uber promised high pay and flexible working hours as a compelling value proposition to independent contractors looking to supplement their income. Venture capitalists were enthralled with the bold ambition of Uber’s disruptive business model, and eagerly jockeyed for the right to invest in the growing, if unprofitable enterprise. Uber raised a record-setting $11.5 billion through 18 funding rounds, ultimately valuing the company at $68 billion. Flush with cash, Uber raced to launch operations in 737 cities across 84 countries, delivering over 5 billion rides as of this writing. There’s a lot to like in this story, except for one thing. The taxi industry that Uber is seeking to disrupt was never profitable when allowed to expand in unregulated markets, reflecting the industry’s low barriers to entry, high variable costs, low economies of scale and intense price competition -- and Uber’s current business model doesn’t fundamentally change these structural industry characteristics. It is indeed ironic that Uber’s fierce determination to avoid regulatory oversight condemns the company to unprofitable operations that the taxi industry experienced during its pre-regulatory era. To see these parallels, a little history is in order. The first gas-powered taxis appeared in New York City in 1907, and began replacing horse drawn carriages in for-hire service. Taxicabs gained momentum when the affordable Ford Model T was introduced shortly thereafter, ushering in a wave of new low-price taxi operators. This posed a serious threat to incumbent taxi companies wedded to higher cost automotive fleets, which precipitated violent protests in many major metro areas in support of regulations to severely constrain new entrants to the taxi market. Sound familiar? Although a few cities legislated restrictions on the permissible number of taxi operators, the largest U.S. taxi market – New York City – remained largely unregulated well into the 1930’s. With the onset of the Great Depression, many unemployed workers turned to the taxi industry to try to earn a living. The resulting oversupply of taxis led to a collapse of fares, as taxi companies and drivers competed in a race to the bottom to attract additional customers. Driver net income and taxi company profits evaporated, the quality of drivers, cars and passenger safety deteriorated, and taxi oversupply exacerbated congestion on city streets. This historical experience exhibits several parallels to Uber’s current business model, presaging the company’s dismal financial performance. The pre-regulated taxi industry was characterized by bounded demand, abundant supply, relatively undifferentiated service quality, extremely low barriers to entry, low customer switching costs, high variable costs and virtually no economies of scale. Many of these same conditions exist today for Uber and its competitors in the shared-ride market. While both then and now, consumers benefitted from low fares and short wait times, structural industry characteristics precluded profitable operations in both unregulated eras. To “fix” this problem eighty years ago, New York City (and many other major metros) made a political decision to favor taxi companies and drivers at the expense of city residents. The Haas Act of 1937 established a licensing system, requiring a medallion for every taxi in New York City, and made it illegal to operate without one. This proved highly lucrative to the government, which sold the medallions in public auctions, and to successful bidders who could operate comfortably with the assurance of tight controls over competition. Originally, New York set a limit of 16,900 taxi medallions, reducing that number to 11,787 after World War II. Fifty years later, the medallion cap was inched up to 11,900, and today, remains capped at 13,587. In contrast, absent regulatory oversight, the current number of shared ride cars operating in NYChas swelled to well over 60,000. The impact of regulations arbitrarily capping taxi supply in NYC has been significant. While the population of New York City grew by 20% since the passage of the Haas Act in 1937, over the same period, the regulated cap on taxi medallions shrank by 20%. As a result, consumers have been subjected to longer wait times, higher fares, deteriorating vehicle quality and shoddy service, while incumbent taxi operators enjoyed escalating profits and soaring medallion values. This is clearly evident in the secondary market for NYC taxi medallions, which serves as leading indicator of expected industry profitability. Between 1975 and 2013 (largely pre-dating Uber's entrance), medallion prices in NYC increased by over 2,700%, far outpacing the growth of the Dow Jones stock price index. But Uber’s aggressive NYC launch in 2011 ushered in a return to unregulated car service expansion, dramatically improving urban mobility at lower prices, but dragging the industry back to an era of profit-killing competition. Not surprisingly, NYC medallion prices collapsed, from a peak of $1.4 million in 2014 to as little as $150,000 three years later. And, in sharp contrast to the growing value of taxi medallions prior to Uber’s launch, the stock price of Medallion Financial Inc. -- a publicly traded company which finances and trades in taxi medallions – collapsed by 85% over the past five years, while the Dow Jones stock price index appreciated by 47%. In historical context, Uber’s extraordinary losses are thus not just a case of growing pains of an ambitious Silicon Valley startup, but a reflection of the deep structural deficiencies in ride-hail industry economics. Prior to artificial regulatory supply caps, the unregulated taxi industry was unprofitable and subject to growing concerns over negative externalities. Uber is now facing the same relentless drag on its P&L. Supporters of Uber’s unfulfilled potential often point to Uber’s first mover advantage, strong network effects, asset-light business model, continued revenue growth and adjacent business expansion opportunities as reasons to expect a near-term turnaround. But none of these factors reverse the fundamental weaknesses in Uber’s business model. For example, conventional wisdom has held that Uber would enjoy a global winner-take-most outcome because of their outsized balance sheet and strong network effects. But to the extent that network effects exist, they are local, not global. For example, the fact that Uber enjoys an 89% market share in Tampa, doesn’t help them in Portland, where Uber’s market share is trending below 50%. In fact, Uber has struggled to achieve market share leadership in many large foreign markets, including China, India, SE Asia and Brazil. Moreover, while network effects do exist within each metro market, the benefits are significantly weakened by extremely low switching costs, which enable drivers and riders to utilize whichever ridesharing service offers the best deal on any given trip. While Uber’s business model has created enormous value for consumers, propelling the company’s rapid growth, its extremely aggressive pricing simply doesn’t generate enough revenue to deliver attractive compensation to drivers and sizable profits to shareholders. By pricing its services 30% or more below comparable taxi fares and then retaining 25% of gross bookings for itself, Uber has squeezed the revenues available to compensate drivers, who are ultimately responsible for providing the labor, equipment, maintenance, insurance and fuel to serve consumers. There is nothing in Uber’s business model that promises to reduce the factor costs of its ridesharing service, nor are there inherent economies of scale that would lower unit operating costs with continued growth. This leads to an inherent conflict between the business objectives of Uber and its drivers. Uber’s revenues are directly proportional to the number of trips it can facilitate, and thus the company has strong incentives to continuously scale its business. Drivers of course want to maximize their revenue per hour worked. But as Uber continues to recruit drivers, the revenue potential per driver inevitably declines. As the highest revenue-generating neighborhoods become increasingly saturated, new drivers are forced to seek less attractive service territories to find customers. These business model dynamics underscore the bleak earnings outlook for Uber drivers. A recent study found that Uber’s net driver compensation in three US major metropolitan areas in late 2015 was only $8.77 - $13.17 per hour, and this was before Uber instituted significant fare cuts in 2016. Uber’s low and declining pay has been a leading cause of Uber’s low driver satisfaction and growing turnover, both in absolute terms and relative to its main competitor, Lyft. There are two possible remedies to improve driver compensation, but both alternatives would undoubtedly harm Uber’s already tenuous economics. Uber could raise fares at its current revenue sharing split, or increase the driver share of gross revenues. Given the structural characteristics of the ride share industry – limited perceived product differentiation, fare transparency, low consumer switching costs and loyalty, and intense competition– Uber has been understandably reluctant to unilaterally raise fares. In fact, Uber and Lyft have been engaged in a race to the bottom on fare cutting and price promotions, reminiscent of the pre-regulatory taxi industry of yore. But urban transport demand isn’t elastic, so ridesharing price cuts have harmed driver compensation, which was the issue at the heart of the heated argument between Travis Kalanick and an Uber driver last year, that became a viral media sensation. As for raising drivers’ revenue share, Uber and its drivers are locked in a zero sum game that leaves little room for generosity on either side. In fact, Uber’s temporary profit margin improvement in 2016 (albeit still yielding steep losses) was primarily driven by its decision to cut driver compensation rates. From its inception, Uber has consistently favored consumer satisfaction over driver welfare – for example, evidenced by its longstanding reluctance to allow in in-app tipping, which even now is poorly executed – which has taken a heavy toll on driver satisfaction and retention. Recent studies have indicated that Uber’s U.S. driver churn has sharply increased this year, to rates as high as 96%. Needless to say, it’s hard (and costly) to maintain double-digit growth rates, when only 4% of mission critical, de facto employees stay on the job for more than a year. As a result, Uber has been forced into perennially aggressive recruitment efforts, offering signup bonuses that can run well in excess of $1,000 (on top of normal compensation) for new drivers. There is little reason to expect near term relief in Uber’s escalating driver recruiting costs (including the expense to maintain hundreds of physical “greenlight hub” locations that provide onboarding support) in the coming years, especially since Uber faces vigorous competition from other enterprises also recruiting part-time drivers, including Lyft, Instacart, DoorDash, Postmates, Grubhub and Amazon Flex. Multiple management missteps have further hindered Uber’s performance, fueling growing distrust from customers, drivers and regulatory agencies. But Uber’s existential challenge remains its broken business model, which is increasingly testing the patience and confidence of its investors. At its current burn rate, Uber cannot survive more than two years without additional injections of capital, which is highly improbable at anything like its current valuation. From the beginning, Uber made a calculated bet that it could achieve global domination, wiping out both incumbent taxi companies and competing shared ride providers, to be able to exercise monopoly pricing power in hundreds of metropolitan markets. But it now appears Uber has lost this bet in its headlong rush into an industry that has historically exhibited low profit potential. Uber is hardly alone in its sisyphean quest for profitability. Every major ridesharing company in the world is still experiencing steep losses after five or more years of operation, including Lyft (U.S.), Ola (India), 99 (Brazil), and Didi Chuxing (China). In Didi's case, the company continues to lose (and raise) money despite its dominant market share, after buying out Uber's Chinese operations 15 months ago. But reaffirming the low barriers to entry in this sector, other well capitalized competitors (UCAR, Meituan) have stepped up their operations, prolonging profit-killing competition for passengers and drivers in the Chinese ridesharing market. There are undoubtedly defensible segments of the global rideshare market that can currently sustain profitable operations. And in the foreseeable but distant future, autonomous vehicle technologies may improve industry economics. But for now, CEO Dara Khosrowshahi will need some serious soul-searching to rethink Uber’s soaring ambition and penchant to win-at-all-costs in all markets. On its current course, Uber’s bridge to global domination is simply a bridge too far. There’s a lot to like about the U.S. economy. Corporate profits are at their highest level in fifty years. The Dow surged past 20,000, continuing the second longest bull market run in history. And the unemployment rate is currently inching towards its lowest level in a decade.

But there are headwinds that have roiled the American electorate. The US economy grew only 1.6 percent in 2016, continuing a generally downward trend over the past 30 years. Real wage growth remains stubbornly elusive, income inequality is at its highest level since the Great Depression and customer satisfaction with the nation’s goods and services is just beginning to recover from a ten-year nadir reached in 2015. These dichotomous results call into question our national and corporate priorities: why isn’t corporate prosperity translating into broader societal well-being? The answer lies partly in two pervasive management practices that have unwittingly compromised long-term national growth and tilted the scale towards corporate benefits at the expense of consumer and employee welfare:

The Economist reports that a $10 trillion acquisition binge since 2008 has contributed to increasing concentration in two-thirds of the US economy’s roughly 900 industries, including cable television, railroads, pharmaceuticals, industrial chemicals, telecom, media, hotels, health insurance and hospitals. Not surprisingly, the resulting decrease in competition has conveyed greater pricing power to many bulked-up incumbents, helping to drive up corporate profits. Take the airline sector for example, long considered an unattractive industry that failed to earn its cost of capital in the thirty years following industry deregulation. As Richard Branson once quipped, "if you want to be a millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline." But a wave of mergers between 2008 and 2012 allowed the three remaining legacy airlines (American, Delta and United) to reduce capacity, raise fares, increase load factors and dramatically improve profitability, despite chronically abysmal customer satisfaction. Since 2012, a weighted index of U.S. airline industry stocks has grown three times faster than the S&P 500. And last year, Branson’s Virgin America agreed to be acquired by Alaska Airlines, further thinning the ranks of U.S. air carriers. Ordinarily, rising profitability would be a cause for celebration, but for two nagging concerns. First, increasing the concentration of corporate profits in fewer oligopolistic hands can stifle innovation, limit consumer choice and increase prices. As a case in point, after AT&T’s proposal to acquire T-Mobile was blocked by the Justice Department in 2011, T-Mobile used its breakup fee windfall to upgrade its network, introduce a number of creative, customer-pleasing rate plans and cut prices. As a result, T-Mobile has increased its market share by 60 percent over the past five years, at the expense of industry market leaders. In pressing for the merger, AT&T had argued that it couldn’t justify investments to upgrade its own 4G-network without first spending $39 billion to acquire T-Mobile. But in reality, intensifying competition, not greater concentration induced AT&T to upgrade its wireless infrastructure over the past five years. And Verizon just announced it would offer unlimited data plans to match popular rate plans offered by T-Mobile and Sprint. Given robust competition, US wireless rates have come down and customer satisfaction has gone up since the AT&T/T-Mobile acquisition was blocked. Often, large horizontal mergers are defensive responses by companies mired in mature, low or negative growth industries. In such cases, mergers are perceived to provide opportunities to “buy” growth, to exploit cost-reducing synergies, and to improve profits as a result of reduced competition and higher price realization. But the resulting corporate behemoths often become even more wedded to status quo business practices, preventing investments in disruptive new products and business models that might cannibalize current market leading positions. A related concern with growing industry concentration is that fewer firms are earning more cash flow than they are able or willing to invest in organic growth. As a result, more capital has flowed to share buybacks of dubious value, and to executive compensation, exacerbating already high levels of income inequality. With growing profitability in the short- to medium-term, corporations have increasingly allocated corporate capital to value extraction activities – share buybacks and dividends – at the expense of value creating investments in R&D, growth-driving capital expenditures and worker training. Over the years 2006-2015, the 459 companies in the S& P 500 Index publicly listed over this period expended nearly $4 trillion on stock buybacks, representing 54 percent of net income, plus another 37 percent of net income on dividends, raising legitimate concerns as to whether too many large enterprises have been under-investing in innovation and corporate capabilities to sustain long-term profitable growth. Many corporate executives have personal incentives to boost EPS and short-term stock price over investments in long-term growth. Recent research indicates that executive compensation currently yields an executive-to-average-worker pay ratio amongst the 500 highest paid U.S. executives of almost 1,000:1. At a time when worker pay has been stagnant for decades, when overall corporate revenue growth has been anemic, and when the rates of returns on assets of U.S. firms been declining for a half-century, this highly skewed distribution of benefits raises troubling questions about whether the U.S. has been enjoying profits without prosperity. While big corporations have been getting bigger, the rate of new business formation in the U.S. has been steadily declining for decades. This trend poses significant problems for the U.S. economy for two reasons. First, startups have traditionally been a hotbed of innovation, increasing growth and productivity. And second, young businesses have accounted for nearly all net new jobs created in the U.S in recent years. Older, larger businesses, by comparison, have been shedding almost as many workers as they’ve added, and this trend is likely to be exacerbated with increasing industry concentration. As an example of the limits of large acquisitions to drive profitable growth, consider the case of Pfizer. Entering the new millennium, Pfizer recognized that its weak product pipeline left it vulnerable to the looming patent expirations on its blockbuster drugs. In response, Pfizer went on an acquisition binge, spending $357 billion (all figures in 2016 dollars) between 2000 and 2016 to buy several large pharmaceutical competitors, including Warner Lambert, Pharmacia and Wyeth. But Pfizer’s acquisitions also faced declining drug discovery productivity, which worsened under Pfizer management. A 2014 analysis of R&D productivity found that Pfizer was the only top ten pharmaceutical company to experience negative net income returns on R&D investment. As a result, over the past five years, Pfizer’s real revenue and net income has declined by 25 percent and 33 percent respectively. To offset weak earnings, Pfizer escalated its stock buybacks, allocating $42 billion to buy back shares since 2012. Over the same period, Pfizer reduced its inflation-adjusted investments in organic growth: R&D spending by 11 percent and capital expenditures by 18 percent.[1] Pfizer’s situation offers a cautionary tale of the limits of large acquisitions and stock buybacks to generate long-term profitable growth. Despite its massive acquisitions and stock buybacks since 2000 at the expense of investments in organic growth Pfizer has emerged as a smaller, less profitable company whose market value has declined by $160 billion (-45 percent). Is there is a better way to manage for long-term profitable growth? This question has been hotly debated for years, with many observers asserting that too many companies have been managing for short-term results, emphasizing cost control and stock buybacks at the expense of investments future growth. New research, led by a team from the McKinsey Global Institute found that companies that operate with a true long-term mindset have considerably outperformed their industry peers since 2001 across almost important every financial measure. The research team analyzed the operating metrics of 615 non-finance companies that reported continuous results from 2001 to 2015, and whose market capitalization exceeded $5 billion in at least one year. To distinguish between companies that exhibited a short- and long-term management mindset, researchers analyzed five operational and business performance indicators.

The analysis concluded that 27 percent of the sample were managed for the long-term relative to their industry peers over the entire study horizon or clearly became more long-term oriented between the first and second half of the study horizon. The remaining 73 percent of companies exhibited evidence of short-term management priorities. The preponderance of management short-termism reflects growing pressure executives feel to hit near-term targets. A recent executive survey reported that 87 percent of executives and directors feel most pressured to demonstrate strong financial performance within two years or less, 65 percent say short-term pressure has increased over the past five years, and 55 percent of executives and directors in companies lacking a long-term culture say they would delay a new project to hit quarterly targets, even if it sacrificed long-term value. But this bias for short-term results is misguided. The difference in financial performance between companies managed for short- and long-term growth is striking. Among the firms identified as focused on the long term, average revenue and earnings growth between 2001 and 2014 were 47 percent and 36 percent higher, and market capitalization grew 58 percent faster as well. The returns to society and the overall economy were equally impressive. Companies that were managed for the long term added nearly 12,000 more jobs on average than their peers over the study horizon. MGI calculated that U.S. GDP over the past decade might well have grown by an additional $1 trillion if the whole economy had performed at the level the long-term stalwarts delivered — and would have generated more than five million additional jobs. Nearly 65 years ago, GMs CEO Charlie Wilson stated “what was good for the country was good for General Motors and vice versa.” But Wilson’s equivalence between corporate and national welfare is only true if executives effectively manage their enterprises with a long-term mindset committed to continuous innovation, meaningful product differentiation and a corporate culture that promotes corporate agility and market responsiveness. [1] Data for four year period, 2011-2015, latest full year for which capex data is available The time to rethink three widely believed, but outdated management ideas is long overdue.

1. There are “good” and “bad” industries In the late 1970s, Michael Porter’s seminal article on business strategy -- How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy -- established five industry characteristics to explain why some companies are inherently more profitable than others. Porter advised managers to seek out businesses with strong bargaining power over buyers and suppliers, low threats of entry from similar or substitute products, and minimal competition, giving rise to the notion that there are “good” and “bad” industries, more or less conducive to attractive financial results. Take airlines for example, plagued by intense price competition, high structural costs and fickle customers. Most airlines historically failed to earn their cost of capital, and every major legacy carrier has gone bankrupt -- at least once. Who would want to enter such a fraught industry? But if structurally challenged industries are destined to suffer, how can one explain that Southwest Airlines’ market cap since 1980 has grown more than four times faster than the S&P 500 and more than 90 times faster than the airline sector as a whole? If a company’s choice is either to enter a poorly performing industry, playing by the same rules as incumbent market leaders, or to stay out of the business entirely, Porter's advice is well taken. But there’s a third choice: recognizing opportunities to address poorly served customers by playing by a different set of rules. Southwest Airlines initially focused on passengers who neither valued, nor were willing to pay for a broad range of amenities offered by legacy airlines, instead delivering no-frills, efficient and friendly one-class service. Similarly, companies like Casper, Costco, Netflix and Warby-Parker have attacked sources of customer dissatisfaction and/or high costs to prove that there’s no such thing as a bad industry, except if you’re an incumbent mired in an outdated business model. 2. The objective of management is to maximize shareholder value. Perhaps no management principle is preached more dogmatically than that management’s objective should be to maximize shareholder value. But this belief has led too many executives to focus on boosting quarterly earnings and stock prices with actions that compromise long-term growth -- a serious problem that’s been getting worse. For example, 80 percent of CFO’s recently reported that they would cut R&D spending if their company risked missing a quarterly earnings forecast. Moreover, S&P 500 companies have spent an unprecedented $3 trillion on stock buybacks over the past five years, partly at the expense of R&D, capital expenditures for expansion, workforce training and other value-creating activities. Share buybacks increase a company’s short-term EPS – that’s just math -- but there is growing evidence to suggest that excessive stock buybacks can undermine long-term value creation. The real issue here is that maximizing shareholder value should be the outcome, not the driver of management priorities. Corporate strategy should be guided by a customer-centric corporate purpose, a clear articulation of the time horizon for planning, decision-making and capital allocation, and how tradeoffs between stakeholder interests should be resolved. As an example, Jeff Bezos’ first letter to shareholders clearly articulated that Amazon would prioritize long-term market leadership over short-term profitability, and that the company would relentlessly focus on customers. By consistently putting customers at the center of Amazon’s strategy and new business development, the company’s market cap has increased almost 1,000X since its IPO. Customers and shareholders have been exceptionally well served by CEO Bezos’ overarching commitment to a long-term customer-centric corporate purpose. 3. Mature businesses inevitably decline Recent research has found that less than 15 percent of Fortune global 100 companies have sustained above-market growth over multiple decades. Does this suggest a Darwinian form of corporate evolution where large corporations are destined to decline? Those who question the feasibility of long-term growth point to three seemingly immutable marketplace constraints:

These “laws” are not only flawed, but they could become a self-fulfilling prophecy of corporate failure. After all, if managers truly believe that long-term growth is impossible, they will seek to protect and harvest current assets and customers for as long as possible. But such an approach—playing not to lose, rather than playing to win—only serves to hasten the decline of incumbent market leaders, as Kodak, Blockbuster, Sears and others have painfully discovered. But there are counter-examples, where businesses have continued to prosper by maintaining the same core values, entrepreneurial spirit and adaptability that led to their success in the first place:

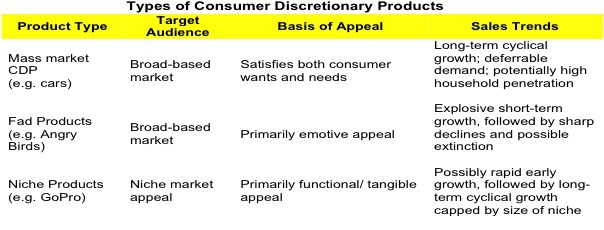

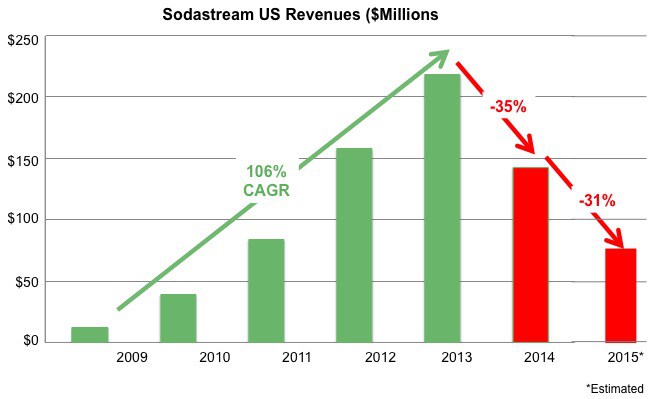

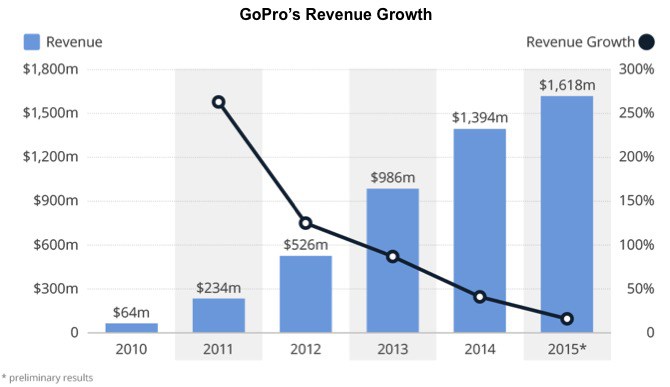

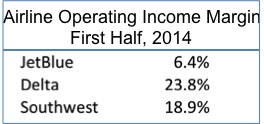

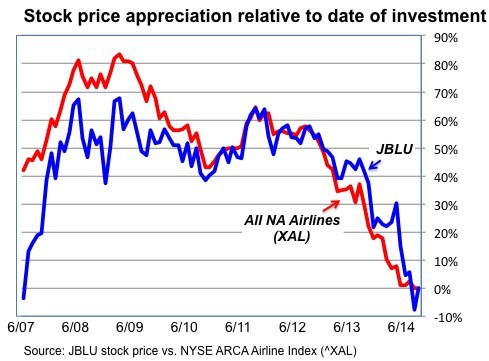

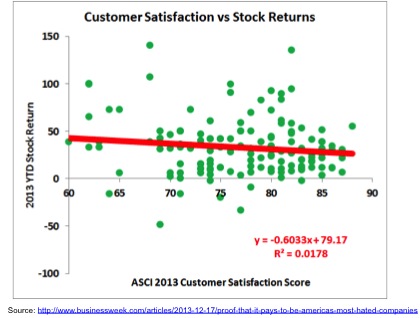

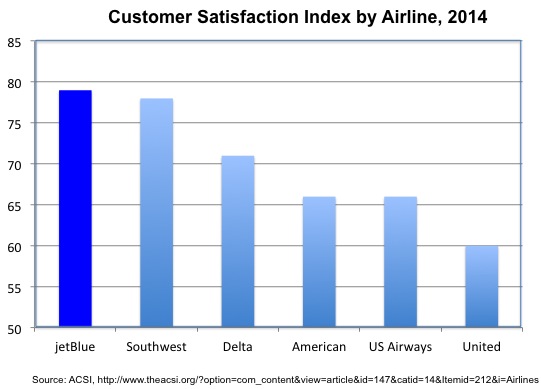

Amazon became the fastest company to exceed $100 billion in sales last year following this approach. Over an even longer term, Johnson & Johnson and 3M are still outpacing overall GDP growth more than a century after their founding. Long-term profitable growth and shareholder value creation is possible in all industries – good or bad.  Within hours of the announcement of the proposed AT&T/Time Warner merger last month, Donald Trump weighed in strongly opposing the deal for concentrating too much power in the hands of too few. It’s understandable that Trump would not want the parent of CNN to amass any more market power. But in a rare instance of policy agreement, Hillary Clinton’s surrogates also signaled immediate antitrust concerns with potential adverse consumer impacts, mindful of widespread populist sentiments in the electorate. On the other side, several business pundits were more bullish, lauding AT&T for responding to the need to do something to strengthen its position in the brutally competitive wireless service provider business, while others suggested now was a good time to secure debt financing to pay for an acquisition, before the Fed raises interest rates. As for Time Warner, its CEO Jeff Bewkes was generally given good marks for securing a higher price for his shareholders than 21 Century Fox was willing to pay two years ago. But none of these hasty pronouncements get at the crux of what would ultimately make this an attractive deal for these two corporate giants. Simply put, the key question is whether the proposed merger will help AT&T and Time Warner to bring better content more efficiently to more customers, faster and at lower prices than either company could provide on their own. The answer is far from clear. AT&T’s CEO Randall Stephenson attempted to preempt the chorus of antitrust concerns by noting that the proposed merger is a case of pure vertical integration, marrying a content provider and a telecom distribution services company that have virtually no direct business overlap. In this regard, the Time Warner deal is fundamentally different from AT&T’s offer five years ago to acquire T-Mobile USA, which was blocked by the Justice Department on fears that the proposed horizontal merger would reduce competition and harm consumers. In retrospect the regulators proved to be right in seeking to protect consumer interests. After being forced to withdraw their acquisition offer, AT&T had to pay a $4 billion breakup fee that T-Mobile used to significantly upgrade its wireless infrastructure. Under the leadership of a new CEO, John Legere, T-Mobile emerged as a fiercely capable competitor, pioneering numerous marketing initiatives giving consumers more flexible mobile services at lower prices. T-Mobile has been growing at AT&T’s expense, adding about 5.5 million new subscribers – nearly three times more than AT&T – over the past eighteen months. While AT&T has been struggling in the competitive, saturated wireless services market, Time Warner also faces the prospect of growing competition for quality content and consumer engagement from traditional and new players, most dauntingly including Facebook, Google, Amazon and Netflix. So both players have legitimate reasons to seek new ways to strengthen their capabilities and relevance amidst industry transformation. AT&T’s CEO notes that “the world of distribution and content is converging and we need to move fast … to curate, [and] to format content differently for [emerging] mobile environments.” Can the proposed vertical integration merger fulfill Randall Stephenson’s vision? Some of the most extraordinarily successful companies in other industries have built their business by exploiting a highly vertically integrated business strategy. Exemplars include Apple, Ikea and Zara, each of whom has been able to deliver superior and unique products to market faster and cheaper, as a result of the extensive assets and capabilities built organically across their value chains over time. But the strategic context underlying the AT&T/Time Warner deal is vastly different. AT&T has traditionally competed vertically by trying to attract as many customers as possible for non-exclusive products and services sold through its branded distribution channels. Time Warner on the other hand is a horizontal player, attempting to attract as many distributors as possible to deliver its proprietary content to market at the highest possible prices. Putting these two companies together creates significant challenges, which provides a very tenuous path to victory. Stephenson’s vision is that the AT&T/Time Warner union will be able to create unique products and services faster and more efficiently, positioning the merged companies to become competitively advantaged. But it will have to do so without unduly eroding the profits Time Warner currently earns by selling proprietary content through competing telecom distribution channels, and without incurring the regulatory wrath of the Justice Department, who has already signaled concerns with growing industry concentration. Threading the needle to satisfy all three of these requirements for a successful deal will not be easy. Wall Street likes businesses with predictable, stable business outlooks. But in assessing the prospects for the proposed merger of AT&T and Time Warner, the reality may be a bit of damned if you do or don’t. Is your business selling a niche, fad or mass market consumer discretionary product? The answer makes a big difference in how to best market and manage growth for new product launches. To explore these product distinctions – and see the consequences of making the wrong bet — consider what a well-known company making action video cameras and another selling home carbonated soft drink machines have in common. Both GoPro and Sodastream priced their IPOs in the low-$20’s, both more than tripled their market value within 9 months, both ran eye-catching Super Bowl ads in 2014 when optimism ran high, but both are now trading at less than 20% of their ephemeral market peaks. It is tempting to add one other obvious similarity: both GoPro and Sodastream sell consumer discretionary products (CDPs), which intrinsically run the risk of falling out of favor. But such a broad-brush categorization is overly simplistic, and warrants further exploration. After all, few CDP companies experience such an exhilarating surge of popularity followed so soon by such a terrifying fall from grace. So it’s important to understand what makes GoPro and Sodastream different from most CDP companies, and what one can learn to avoid their roller coaster ride in the marketplace. What are consumer discretionary products? Consumer discretionary products cater to consumer “wants” rather than staple “needs.” Companies in this sector encompass retailers of non-essential goods and services, media and entertainment, consumer durables, high-end apparel and automobiles, which typically exhibit cyclical performance tied to the health of the broader national economy. After all, by their nature consumer discretionary purchases can be deferred or simply ignored when times get tough. But in fact, CDP businesses have performed extremely well of late. For example, the largest CDP stock index fund in the U.S. doubled in value over the past 5 years (2011-2015), outpacing growth in the overall S&P 500 by more than 2X.[1] So clearly, there have been other circumstances at play affecting the performance of GoPro and Sodastream. A fad perhaps? One popular view, embraced by short-sellers who have owned close to half of GoPro’s and Sodastream’s float, is that both companies sell fad products that were bound to run out of steam as consumers jumped ship in search of the ‘next new thing.’ It turns out that the shorts were right in betting against these stocks, but not because GoPro and Sodastream are fads. Fad products stimulate an unexpected and viral explosion of consumer enthusiasm, leading to skyrocketing sales, followed by an abrupt and equally rapid decline in market interest. We’ve all seen (and probably owned) many fad products over the years. Perhaps the quintessential example was the Pet Rock – a product of mockingly limited value – which wound up selling 1.5 million units during a six-month silly season in 1975 before disappearing from sight. But there have been hundreds of other fad products over the years as well, some of which created immense wealth for their inventors. Take for example the now often forgotten, but once gotta-have fads for kids: Silly Bandz, Koosh Balls and Beanie Babies. Grownups too have had their flings with fad products such as Snuggies, Cronuts and Grumpy Cat merchandise. The common characteristic underlying all fad products is that their basis of mass market appeal is almost strictly emotive (as opposed to functional), and therefore highly subject to the vicissitudes of consumer whim. What’s hip today is decidedly old-school tomorrow. So if you’re lucky enough to launch a successful fad product, enjoy the ride, because it likely won’t last. Niche products How does this apply to GoPro and Sodastream? Neither of these company’s products exhibit the intrinsic attributes of a fad, because they actually deliver tangible functional value to an identifiable niche segment of consumers, rather than temporary emotive appeal to the mass market. In fact, Sodastream has been selling home carbonated drink machines for well over one-hundred years during which its underlying consumer value proposition has hardly fundamentally changed. What did change was that for a brief period following its 2010 IPO, Sodastream misguidedly over-hyped its product and over-expanded its distribution, which created the conditions for the inevitable business crash that followed. Here’s the scenario. Buoyed by access to public capital, Sodastream believed it could dramatically expand its US addressable market by touting its home carbonated soft drink machines as a virtuous alternative to the soda category giants. The marketing team ramped up its advertising and promotion spend, pitching Sodastream home brews as more convenient, sustainable, healthy, cost-effective and personalized than popping open a can of Coke or Pepsi. As sales began to pick up – albeit from a very low base — the company aggressively recruited new retail partners, expanding beyond its initially limited distribution through Williams-Sonoma, to Macy’s, Bed, Bath & Beyond, JCP, Target, Best Buy and Walmart. By 2013, Sodastream’s US retail footprint peaked at nearly 17,000 stores. The company was betting heavily that it could increase its US household penetration at least tenfold from an installed base of around 1%. Sodastream reasoned that its expanded marketing and distribution initiatives could generate mass market appeal, mirroring household penetration rates across Europe that ran as high as 25%. Super Bowl ads soon followed, but starting in 2014, Sodastream’s US sales virtually fell off a cliff. Why did Sodastream fail to fulfill the growth potential envisioned by its CEO? And more puzzlingly, why did Sodastream’s sales trend resemble a fad product rather than the more typical product life cycle where the transition from high growth to maturity to eventual decline often takes many years? The simple answer is that Sodastream (and its retail partners) fundamentally misread the market. They dramatically expanded national distribution as if the challenge was to keep up with explosive mass-market growth, whereas actual consumer demand was limited to a relatively small environmentally-and health-conscious niche of the US market. Much of Sodastream’s reported sales growth in 2012 and 2013 merely reflected the sell-in to stock new retailers’ shelves. When consumer demand failed to materialize, many overstocked retailers simply stopped ordering any new product, which explains Sodastream’s precipitous revenue decline over the past two years. In response, Sodastream has pushed reset on its misguided strategy, significantly scaling back its retail footprint and repositioning its consumer value proposition. As CEO Daniel Birnbaum explains: We’ve completely shifted our strategy from a different way to do soda at home to Water Made Exciting! Americans want to drink more water; that’s what they really want to drink. It’s where the future of beverage is. It’s in a space that doesn’t quite exist today. It’s very small… It’s the space between soda as we know it — sweet or chemical — and still water as we know it. There’s a space there in the middle.[2] One of the mistakes that we made… was that because we address a mass market category, I thought early on that I can go ahead and access the mass market out of the gate and that we can go very quickly to places like Sears, Kmart, Wal-Mart, but really that doesn’t work that way. When you’re building a disruptive category, OK, that has a very unique appeal and it requires a behavior change, one needs to take a more staged approach to the consumer and focus initially on opinion leaders, evangelists, people who are courageous and bold and willing to make decisions that entail some sort of an investment in time and habit change maybe and money and that’s a realization that we have now after we’re already in Wal-Mart.[3] In retrospect, Sodastream would have been far better served if it built its brand, customer base and distribution network at a more measured pace, consistent with the actual niche appeal of its customer value proposition, rather than chasing the misguided dream of mass-market demand. The same lessons learned are now playing out at GoPro, which racked up impressive triple-digit annual growth rates prior to its late-June 2014 IPO. From its inception, GoPro enjoyed extraordinarily high global brand awareness, fueled by hundreds of millions of page views of its breathtaking action videos posted on YouTube and other social media channels. GoPro’s brand name quickly became synonymous with the category it created. As such, investors saw much cause for optimism, propelling GoPro’s stock to nearly $95 within 3 months of its IPO at $24 per share. But alas, while a broad base of consumers undoubtedly enjoyed gawking at GoPro’s exhilarating online videos, far fewer had the lifestyle, budget or need to actually buy and use the pricey video cameras. In fact, GoPro’s sales growth rates had already been steeply declining prior to its IPO. [4] Despite mounting evidence that GoPro was approaching the limits of its niche market appeal, the company continued to launch expensive new models and to rapidly expand its global distribution footprint. By the end of 2015, GoPro hit the wall, announcing that Q4 sales were expected to be nearly 50% below the same period in the prior year (in part reflecting the 50% price cuts it had been forced to make on its newest model), and that the company would be laying off 7% of its work force.[5] As with Sodastream, GoPro drunk its own Kool-Aid and tried to extend its brand, price realization and distribution far beyond the limits of its actual niche market appeal. The company now faces a costly retrenchment that will undoubtedly harm its brand image, retailer relations and investor confidence for years to come. Companies launching a consumer discretionary product should honestly assess whether their new venture is realistically likely to appeal to the mass market or a niche segment. Sodastream and GoPro belatedly discovered that their product was solving a problem that most consumers simply didn’t have. Trying to promote an inherently niche consumer discretionary product to the mass market can be a painfully costly mistake. _________________________________________________________________________________ [1] http://etfdb.com/etfdb-category/consumer-discretionary-equities/ [2] Fortune Magazine interview with CEO Daniel Birnbaum, February 6, 2015; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8WYa1J2G7E [3] “5 Things Sodastream’s Management Wants You to Know,” Investopedia, May 19, 2015; http://www.investopedia.com/stock-analysis/051915/5-things-sodastreams-management-wants-you-know-soda.aspx [4] Richter, Jason, “GoPro Has Trouble Sustaining Its Growth,” Statista, January 14, 2016 [5] Cipriani, Jason, “GoPro’s Shares Suffer Huge Wipeout on Weak Sales, Layoffs,” Fortune Magazine, January 13, 2016 I was chatting with William Shakespeare the other day about Brian Williams when he shared what seemed to be a keen insight: “the fault dear Len is not in our stars but in ourselves. Willy often drops these bewildering aphorisms, leaving me to ponder the hidden meaning. But just this morning, it hit me. Willy understood the real lessons learned from l’affaire Williams. In his effete apology last month, Brian Williams claimed he conflated two separate helicopter missions in his reporting on the Iraq war. Subsequent investigations raised additional concerns with the veracity of his alleged encounters with Seal Team 6, Hurricane Katrina and, sacré bleu, even the Pope. In my view, the ensuing tsunami of moral outrage has been misplaced. We should not blame Brian Williams, the star. The fault is mostly our own. In granting Brian Williams star status, viewers and media pundits have conflated acting with journalism for years. We should never have revered Brian Williams as a serious journalist whose nightly reports could be taken as gospel. Brian Williams is an actor. So is Bill O’Reilly (provocateur) and Jon Stewart (comedian). Each has a shtick that has served them and their TV ratings well. The reason why The Daily Show is so beloved and Williams is now scorned is that Jon Stewart never pretended to be a serious political commentator (although in many ways he was). Stewart is a talented comedian who delivers an irreverent perspective on the news, as often directed towards newscasters as newsmakers. Brian Williams’ shtick was gravitas. His act portrayed him as a serious and inquisitive on-air journalist to be trusted to tell it like it is. But of course, Brian Williams’ on-air persona was just an act, not the work of a serious investigative journalist. In playing his role, Williams felt obliged to create photo-ops at the scene of major stories – Katrina, Iraq, Vatican City – as if his very presence confirmed the importance of the event. After all, if Brian Williams told us he got dysentery after accidentally ingesting tainted water in New Orleans, we just knew Katrina was a serious hurricane, 1,833 fatalities notwithstanding. In retrospect, it was ludicrous for viewers to expect Brian Williams to deliver remarkable scoops during his 36-hour whirlwind tours through New Orleans or Middle East war zones that were somehow missed by other serious journalists. You can’t blame Williams for wanting to share sightings of dead bodies floating down flooded streets in New Orleans or hanging out with Seal Team 6 or chatting with the Pope. Nightly News viewers would expect no less from a man of such gravitas. We wanted to believe that Williams could bring gripping stories to our TV screens nightly. So we put Williams in an impossible spot; to be something he wasn’t and couldn’t be. Sure Brian Williams is an egotist who ultimately drunk his own Kool-Aid. But we were enablers every step of the way. Our anger now is probably rooted in recognizing our own foolishness. The Brian Williams show is over. Going forward, I hope his replacement neither aspires to be a superstar, nor conflates his or her flyby photo-ops with real reporting. I think Sergeant Joe Friday got it right when I recently asked him what he hoped to get from NBC Nightly News going forward. “Just the facts, Len; just the facts.” Being the CEO of a publicly traded enterprise requires a delicate balancing act to keep multiple stakeholders happy, namely shareholders, customers and employees. Dave Barger has been walking this tightrope for seven years as CEO of jetBlue, doing an admirable job building a profitable, growing airline that customers love to fly. This year, jetBlue earned the J.D. Power award for highest customer satisfaction among Low Cost Carriers in North America for the 10th straight year, reflecting the airline’s numerous customer-friendly perks:

According to Bloomberg BusinessWeek, “several analysts have consistently suggested the shares are depressed because of Barger’s focus on passenger-friendly initiatives that leave shareholders at a disadvantage.” Fortune Magazine echoed these sentiments, reporting “above all, {analysts} hate that JetBlue provides the most leg room of any domestic U.S. carrier in coach, with a seat pitch of 33 inches standard. By comparison, the legacy carriers have cut their seat pitch in coach down to 30 inches, which has allowed them to stuff more seats on their planes… {Analysts} view Dave Barger, JetBlue’s chief executive, as being “overly concerned” with passengers and their comfort, which they feel, has come at the expense of shareholders.” Wolfe Research chimed in with additional advice to management: “JetBlue has ample opportunities to unlock value including a first checked bag fee, increasing seat density, cutting capex, dropping hedging, simplifying the fleet, and overbooking… to name a few.” Some analysts such as Helane Becker of the Cowan Group have gone even farther, openly calling for Barger’s head: “We believe a management change would lead to a change in philosophy and likely morph the model similar to one of Spirit Airlines although not as extreme.” This week, Wall Street naysayers got their wish, as jetBlue announced that Barger’s contract would not be renewed. In February, Robin Hayes, jetBlue’s COO will succeed Barger as CEO, perhaps presaging a concerted pruning of jetBlue’s signature passenger-friendly perks. This melodrama is reminiscent of Wall Street angst towards Amazon, where many analysts also feel that CEO Jeff Bezos has also been putting the welfare of customers ahead of shareholders. For example, Slate columnist Matthew Yglesias has called Amazon ”a charitable organization being run by elements of the investment community for the benefit of consumers.” Since when has superior customer service become viewed as a management liability? CEO’s like Dave Barger and Jeff Bezos have managed their companies with a decided bias towards long-term value creation, brand distinctiveness and customer loyalty, rather than short-term profit maximization. In this regard, Barger’s track record is actually considerably better than assessed by jetBlue’s critics. In May, 2007, Barger inherited a seriously over-extended airline that was reeling from an existential crisis of mortifying customer service meltdowns. Barger had to engineer a turnaround during a severe depression that wreaked havoc on airline balance sheets and income statements for at least three years, ultimately driving American, Frontier, Aloha and others into bankruptcy. But by 2011, the results of Barger’s transformation of jetBlue were clearly evident. The figure below compares jetBlue’s stock price appreciation vs. the North American airline industry as a whole during Barger’s tenure. As shown, stockholders who invested in JBLU on or after January 3, 2011 have enjoyed returns at or mostly above the industry as a whole through September, 2014. Nonetheless, many on Wall Street have appeared to lose patience with Barger’s inability to convert industry leading levels of customer satisfaction into even higher growth in revenue and profits. Dave Barger is not alone in struggling with this challenge. One would like to believe that superior customer satisfaction is a competitive advantage that can help drive higher customer loyalty, word-of-mouth referrals, increased new customer acquisition, all at higher prices and profit margins. In reality though, demonstrating this linkage has proven difficult for many companies, and at best requires a long timeframe to make the case. Moreover, contrary examples abound. For example, companies with strong monopoly/oligopoly positions often exploit their market power to achieve high margins, despite horrific customer service. Take Time Warner Cable (TWC) for example, a perennial rock-bottom loser in customer satisfaction studies. Despite widespread customer abuse, TWC’s share price has grown >250% over the past five years. More broadly, the American Customer Satisfaction Institute conducts annual surveys of customer satisfaction across multiple industries using a common battery of metrics. Comparing company-specific customer satisfaction measures for 146 companies in 2013 with their stock price appreciation during the year yields the following discouraging results. There is virtually no relation between a company’s measured ability to satisfy customers and its stock price appreciation. In fact, a regression between these two variables yields a slightly negative relationship. As noted at the outset, managing a complex enterprise requires a delicate balancing act to serve the often-competing interests of customers, shareholders and employees.[1] jetBlue undoubtedly can and will find additional mechanisms to raise revenues in the months ahead, but hopefully will do so in a manner consistent with its customer-friendly brand persona that has distinguished the airline since its founding. Calls for jetBlue to jam more seats into their aircraft and to mimic standard industry practice of charging fees for every conceivable service would render jetBlue no different from its peers, whose track record in delivering satisfactory customer service is quite poor. As shown below, jetBlue is currently a US industry leader in airline customer satisfaction. jetBlue has invested heavily in creating an exceptionally strong customer franchise, built on a solid foundation of valued service. The challenge now is to determine how to extract more value from this strong position, without losing jetBlue’s brand essence or corporate soul. Some sage advice from Michael O’Leary, CEO of low cost airline Ryanair is apropos here: “If you don’t approach air travel with a radical point of view, then you get in the same bloody mindset as all the other morons in this industry. This is the way it has always been and this is the way it has to be.” Maintaining meaningful differentiation is essential for jetBlue to build on its distinctive brand character. Finding the right tradeoffs between increased revenue realization and valued customer service offerings will continue to be a delicate balancing act for jetBlue’s new CEO. _____________________________________________________ [1] In April, jetBlue’s pilots voted to join the ALPA union, highlighting another conflict in balancing the objectives of management and the company’s stakeholders. |

Len ShermanAfter 40 years in management consulting and venture capital, I joined the faculty of Columbia Business School, teaching courses in business strategy and corporate entrepreneurship Categories

All

Archives by title