Within hours of the announcement of the proposed AT&T/Time Warner merger last month, Donald Trump weighed in strongly opposing the deal for concentrating too much power in the hands of too few. It’s understandable that Trump would not want the parent of CNN to amass any more market power. But in a rare instance of policy agreement, Hillary Clinton’s surrogates also signaled immediate antitrust concerns with potential adverse consumer impacts, mindful of widespread populist sentiments in the electorate. On the other side, several business pundits were more bullish, lauding AT&T for responding to the need to do something to strengthen its position in the brutally competitive wireless service provider business, while others suggested now was a good time to secure debt financing to pay for an acquisition, before the Fed raises interest rates. As for Time Warner, its CEO Jeff Bewkes was generally given good marks for securing a higher price for his shareholders than 21 Century Fox was willing to pay two years ago. But none of these hasty pronouncements get at the crux of what would ultimately make this an attractive deal for these two corporate giants. Simply put, the key question is whether the proposed merger will help AT&T and Time Warner to bring better content more efficiently to more customers, faster and at lower prices than either company could provide on their own. The answer is far from clear. AT&T’s CEO Randall Stephenson attempted to preempt the chorus of antitrust concerns by noting that the proposed merger is a case of pure vertical integration, marrying a content provider and a telecom distribution services company that have virtually no direct business overlap. In this regard, the Time Warner deal is fundamentally different from AT&T’s offer five years ago to acquire T-Mobile USA, which was blocked by the Justice Department on fears that the proposed horizontal merger would reduce competition and harm consumers. In retrospect the regulators proved to be right in seeking to protect consumer interests. After being forced to withdraw their acquisition offer, AT&T had to pay a $4 billion breakup fee that T-Mobile used to significantly upgrade its wireless infrastructure. Under the leadership of a new CEO, John Legere, T-Mobile emerged as a fiercely capable competitor, pioneering numerous marketing initiatives giving consumers more flexible mobile services at lower prices. T-Mobile has been growing at AT&T’s expense, adding about 5.5 million new subscribers – nearly three times more than AT&T – over the past eighteen months. While AT&T has been struggling in the competitive, saturated wireless services market, Time Warner also faces the prospect of growing competition for quality content and consumer engagement from traditional and new players, most dauntingly including Facebook, Google, Amazon and Netflix. So both players have legitimate reasons to seek new ways to strengthen their capabilities and relevance amidst industry transformation. AT&T’s CEO notes that “the world of distribution and content is converging and we need to move fast … to curate, [and] to format content differently for [emerging] mobile environments.” Can the proposed vertical integration merger fulfill Randall Stephenson’s vision? Some of the most extraordinarily successful companies in other industries have built their business by exploiting a highly vertically integrated business strategy. Exemplars include Apple, Ikea and Zara, each of whom has been able to deliver superior and unique products to market faster and cheaper, as a result of the extensive assets and capabilities built organically across their value chains over time. But the strategic context underlying the AT&T/Time Warner deal is vastly different. AT&T has traditionally competed vertically by trying to attract as many customers as possible for non-exclusive products and services sold through its branded distribution channels. Time Warner on the other hand is a horizontal player, attempting to attract as many distributors as possible to deliver its proprietary content to market at the highest possible prices. Putting these two companies together creates significant challenges, which provides a very tenuous path to victory. Stephenson’s vision is that the AT&T/Time Warner union will be able to create unique products and services faster and more efficiently, positioning the merged companies to become competitively advantaged. But it will have to do so without unduly eroding the profits Time Warner currently earns by selling proprietary content through competing telecom distribution channels, and without incurring the regulatory wrath of the Justice Department, who has already signaled concerns with growing industry concentration. Threading the needle to satisfy all three of these requirements for a successful deal will not be easy. Wall Street likes businesses with predictable, stable business outlooks. But in assessing the prospects for the proposed merger of AT&T and Time Warner, the reality may be a bit of damned if you do or don’t.

0 Comments

I was chatting with William Shakespeare the other day about Brian Williams when he shared what seemed to be a keen insight: “the fault dear Len is not in our stars but in ourselves. Willy often drops these bewildering aphorisms, leaving me to ponder the hidden meaning. But just this morning, it hit me. Willy understood the real lessons learned from l’affaire Williams. In his effete apology last month, Brian Williams claimed he conflated two separate helicopter missions in his reporting on the Iraq war. Subsequent investigations raised additional concerns with the veracity of his alleged encounters with Seal Team 6, Hurricane Katrina and, sacré bleu, even the Pope. In my view, the ensuing tsunami of moral outrage has been misplaced. We should not blame Brian Williams, the star. The fault is mostly our own. In granting Brian Williams star status, viewers and media pundits have conflated acting with journalism for years. We should never have revered Brian Williams as a serious journalist whose nightly reports could be taken as gospel. Brian Williams is an actor. So is Bill O’Reilly (provocateur) and Jon Stewart (comedian). Each has a shtick that has served them and their TV ratings well. The reason why The Daily Show is so beloved and Williams is now scorned is that Jon Stewart never pretended to be a serious political commentator (although in many ways he was). Stewart is a talented comedian who delivers an irreverent perspective on the news, as often directed towards newscasters as newsmakers. Brian Williams’ shtick was gravitas. His act portrayed him as a serious and inquisitive on-air journalist to be trusted to tell it like it is. But of course, Brian Williams’ on-air persona was just an act, not the work of a serious investigative journalist. In playing his role, Williams felt obliged to create photo-ops at the scene of major stories – Katrina, Iraq, Vatican City – as if his very presence confirmed the importance of the event. After all, if Brian Williams told us he got dysentery after accidentally ingesting tainted water in New Orleans, we just knew Katrina was a serious hurricane, 1,833 fatalities notwithstanding. In retrospect, it was ludicrous for viewers to expect Brian Williams to deliver remarkable scoops during his 36-hour whirlwind tours through New Orleans or Middle East war zones that were somehow missed by other serious journalists. You can’t blame Williams for wanting to share sightings of dead bodies floating down flooded streets in New Orleans or hanging out with Seal Team 6 or chatting with the Pope. Nightly News viewers would expect no less from a man of such gravitas. We wanted to believe that Williams could bring gripping stories to our TV screens nightly. So we put Williams in an impossible spot; to be something he wasn’t and couldn’t be. Sure Brian Williams is an egotist who ultimately drunk his own Kool-Aid. But we were enablers every step of the way. Our anger now is probably rooted in recognizing our own foolishness. The Brian Williams show is over. Going forward, I hope his replacement neither aspires to be a superstar, nor conflates his or her flyby photo-ops with real reporting. I think Sergeant Joe Friday got it right when I recently asked him what he hoped to get from NBC Nightly News going forward. “Just the facts, Len; just the facts.” Intense media coverage of the standoff between Amazon and French publisher Hachette over ebook pricing has called into question who will control the future of the book industry. This debate has historical precedent. The invention that enabled the creation of the modern book publishing industry – the Gutenberg printing press – was ridiculed at its inception by the prior gatekeepers of the printed word. Monks who transcribed scriptures and religious writings by hand once controlled both the editorial and distribution functions in what was the parchment, if not the book industry. As with Hachette today, it is understandable that artisanal monks felt threatened by a new technology, which allowed laypersons to print and distribute any document at far lower cost. We have seen similar cases of technological disruption throughout history, be it combine harvesters and threshers that accelerated the agricultural revolution at the expense of family farmers, or Sam Walton’s big box retailing innovations that dislodged thousands of mom-and-pop retailers, or Internet news aggregators that are posing grave threats to today’s metro and national newspapers. In each of these transitions, critics – either businesses directly disrupted by new technologies or citizens wedded to traditional mores — have rightfully called attention to what is being lost in exchange for supposed progress. For example, some critics of inaugural telephone services feared that families would become asocial, no longer needing personal visits to communicate with friends and neighbors. One can only imagine how such luddites would feel today about text messaging and social networking! It is ultimately up to the consumer marketplace, moderated as necessary by regulators and the courts, to decide on the pace and direction of technological progress. Under any circumstances however, new technologies that undermine historical bases of competitive advantage are highly disruptive not only to the incumbents’ business economics, but to their emotional well-being as well. If one has spent an entire career mastering complex skills and business relationships only to find these assets diminishing in value, the impacts are viscerally disorienting and threatening. These dynamics are once again at play in the negotiations between Amazon and Hachette. But the roots of this dispute go much deeper than ebook pricing terms, and the stakes pose an existential threat for book publishers. The question is, what can publishers learn from history to guide the way forward? To understand this high stakes game, it’s important to start with the historical context underscoring the publishing industry’s dilemma and challenge. For starters, the book publishing industry was caught in a broken business model of their own making, long before Amazon introduced its first Kindle in 2007. Decades ago, publishers adopted an inherently costly business model whereby books were sold on consignment to bookstores. With thousands of releases each year added to an even larger backlist, it has always been extremely difficult to predict the popularity of any given new title. Either bookstores or publishers had to assume the risk of getting new titles on retailers’ shelves. With production economics favoring large print runs, publishers bit the bullet, allowing free returns from bookstores, and have lived with the costly consequences ever since: return rates averaging 40% across the industry. Facing chronic slow growth and anemic profitability, independent publishers were acquired by large media conglomerates (e.g. CBS, Bertelsmann, News Corporation), who by 2000 controlled over 80% of total book production. Backed by stronger balance sheets, book publishers increasingly focused their efforts on blockbuster hits, funneling multi-million dollar advances to established authors. But as competition drove up the bidding, publishers continued to struggle to earn attractive returns, typically losing money on over 70% of new releases. Moreover bigger bets on populist blockbusters meant fewer resources were available to support up-and-coming authors with advances, marketing, PR and promotions. Thus the industry’s storied past of cultivating great literature has been under pressure for decades, quite apart from the threat of ebooks or Amazon. To compound their woes, book publishers failed to anticipate and have been slow to effectively respond to the transformation of the publishing industry in the post-Kindle era. In November 2007, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos launched the original Kindle, surprising publishers with plans to price new ebook releases and best sellers at $9.99, well below the wholesale price publishers charged Amazon. With its aggressive, loss-leader pricing, wide selection and heavy marketing, ebook sales skyrocketed and Amazon’s market share reached nearly 90% within two years, alarming publishers. In response, in January, 2010, Hachette and four other publishers announced an agreement with Apple, whereby publishers would set retail prices for ebooks – typically 30% higher than Amazon’s prices at the time – giving retailers a fixed agency commission on each sale. But t he Department of Justice filed suit in April 2012, claiming Apple and the five publishers were guilty of collusive price-fixing. Hachette was one of three publishers that immediately chose to settle, restoring Amazon’s freedom to set ebook prices and agreeing to renewed negotiations after a two-year “cooling off” period, bringing us to today’s standoff between Amazon and Hachette. As digital penetration of the overall trade book industry approaches 50%, publisher profits have actually been strengthening, reflecting lower paper, print and binding costs and fewer unsold returns. But even if publishers temporarily succeed in maintaining their margins in the current round of negotiations, a far larger concern is the uncertain role legacy publishers will play, as printed books inevitably become an ancillary component to an ebook-dominated marketplace. The publishers’ longstanding source of market dominance has been their editorial gatekeeping function that historically dictated which books would be published at a scale requiring capital-intensive printing plants, and their distribution network that could rapidly place printed books on thousands of bookstore shelves. But with the advent of digital book production and distribution, these assets are no longer as valuable as they used to be, nor do they serve as effective barriers to competition. Thus, despite the recent tsunami of negative press being directed towards Amazon, this dispute is ultimately not about whether Amazon is a monopolist or monopsonist. Nor is it about whether Amazon is trying to use books as a loss leader to sell other merchandise or whether the company is treating Hachette, authors or its own customers fairly. It is also not about whether book publishers as currently configured are an essential bedrock of our society. It is about whether publishers can retool their business capabilities to maintain a vital role in adding value to all stakeholders in an industry where books will increasingly be produced, marketed, reviewed and sold in profoundly different ways. What does this mean in practical terms? Many authors who once would have been thrilled to be offered a legacy publisher contract are now asking: “what can you do for me that I can’t obtain elsewhere?” Publishers are quick to point out their longstanding editorial excellence, which will undoubtedly continue to be important. But to succeed in the post-digital era, publishers will also need to excel in customer relationship marketing, exploitation of social media, video production and promotion, multi-media web design and virtual book promotion as well as increasing the efficiency of their business operations and offering far more competitive digital book royalties. Right now, digital publishing capabilities are being driven and refined by a wide range of new competitors – native epublishers, enterprising self-published authors and a host of specialists providing a la carte services, including cover design and graphics, editing/copyediting, fact checking, videography, digital marketing, business analytics and market trend analysis. Publishers who continue to focus their attention and anger on Amazon rather than on the broader forces reshaping the book publishing industry are in grave danger of losing their battle for relevance and possibly survival. The imperative now is to build new skills necessary to survive and prosper in this rapidly changing industry. Publishers need to get beyond defending their nobility while demonizing Amazon, and start fighting more effectively on the new battlefield. As a fight over ebook pricing intensifies between French book publisher Hachette and online retailer Amazon (AMZN), some are suggesting that Amazon customers are being left behind. While details of the ongoing standoff are sketchy, it has become clear that Amazon is pressuring Hachette by making access to its books difficult on amazon.com. As an author whose recent book was published by Hachette, Fortune’s Adam Lashinsky penned an article earlier this week that takes issue with Amazon’s behavior as contrary to the company’s ostensible obsession with customer service. I would argue that he is confusing “anti-consumer” with “fierce competitor” in characterizing Amazon’s behavior. By way of background, this dispute dates back to November, 2007, when Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos launched the original Kindle, surprising publishers with plans to price new ebook releases and best sellers at $9.99, well below the wholesale price publishers charged Amazon. At the time, publishers charged Amazon and other retailers the same wholesale price for e-books as for hardcovers, typically around $13. With its aggressive, loss-leader pricing, wide selection and heavy marketing, ebook sales skyrocketed and Amazon’s market share reached nearly 90%, alarming publishers. In response, in January, 2010, Hachette and four other publishers announced an agreement with Apple (AAPL), whereby publishers would set retail prices for ebooks – typically 30% higher than Amazon’s prices at the time – giving retailers a fixed agency commission on each sale. The Department of Justice filed suit in April, 2012, claiming Apple and the five publishers were guilty of collusive price-fixing. Hachette was one of three publishers that chose to settle, providing Amazon and other retailers immediate discretion in ebook pricing and agreeing to renewed negotiations after a two-year “cooling off” period, which brings us to today’s riff between Amazon and Hatchette. In his piece, Lashinsky says: “But let’s get back to the customer. Assume for a moment that Hachette is the bad guy here, that the smallest of the major book publishers is making unreasonable demands on Amazon. (This seems unlikely, but bear with me.) Even if Hachette were behaving badly, I’m scratching my head trying to figure out in what strange universe Amazon believes that making it difficult for its customers to buy Hachette’s products is consistent with “customer obsession.” I’m trying to understand how Amazon thinks this will help it “earn and keep customer trust.” I would argue that it’s a mistake to assume there are good guys or bad guys here. I don’t begrudge either side for fighting hard for their own interests. So let’s just look at the impact on consumers if either side gets their way. Hachette might prevail because they have a 100% monopoly on all their titles, and are pushing Amazon very hard with the threat of not selling any of their books at lower wholesale prices. Essentially, Hacehtte’s position for now appears to be: “our way or nothing — if you want our books, here’s the price, period.” If Amazon backs down, they will have to maintain high retail prices to cover high wholesale prices. Keep in mind of course that the publishers set high wholesale prices for ebooks from day one and then illegally colluded with Apple and other publishers to keep ebook retail prices high in 2010. Lashinksy seem to ignore these facts in brandishing Amazon as the anti-consumer player in this dispute. Now if Amazon prevails – despite having the relatively weak bargaining position of controlling only 33% of total book sales – Hachette (and then presumably other publishers) will be forced to lower wholesale prices, which Amazon will likely pass along to consumers. Consumers would be the obvious beneficiaries here, as they are across every product category on amazon.com. Turning Lashinsky’s argument around, I’m trying to understand what strange universe he lives in to believe that consumers won’t come out ahead if Amazon wins this fight. Lashinsky may be conflating author interest with consumer interest, and I can understand his disappointment in being collateral damage in this fight. But as he notes, consumers have alternative choices to buy his book (as I already have). After the dust settles, if Amazon wins, he will wind up selling morebooks at lower retail prices and probably earn higher royalty payments. I think Lashinsky should redirect some of his wrath on Hachette, who, like other major publishers, pays only a 25% royalty rate on e=book sales, compared to 50% from native e-publishers like Open Road Media or 50%-70% from Amazon (depending on ebook price). Right now, publishers are squeezing authors and consumers pretty hard. But it’s just business. I don’t waste a lot of energy worrying whether publishers are anti-consumer. Having said that, I stick with my prediction that major publishers will not be able to win this fight. Amazon has consumers on their side. That’s the universe I live in. The New York Times Editorial Board’s opinion on the recent e-book pricing court decision echoes the publishing industry’s longstanding position: “The big picture is that while Apple’s pact with the publishers raised prices in the short term, it also brought much-needed competition to the e-book marketplace. It is estimated that Apple now controls 10 percent of that market and Amazon 65 percent, with Barnes & Noble and others splitting the rest. That is healthier for the publishers and for consumers, too.” Underscoring the Times’ argument is a widely held, visceral conviction amongst publishers that Amazon’s growing share of the market for both paper and digital books has been bad for the industry, for consumers and even for society as a whole, given the hallowed role of the written word in our lives. However passionately held these beliefs are, they ultimately were deemed to hold little legal merit, as U.S. District Court Judge Denise Cote ruled decisively against Apple in the antitrust case — and by extension, against the publishers who had already settled to avoid mounting legal costs. While the penalty ruling has yet to be rendered, Judge Cote left no doubt that this case was not even a close call in her blistering 160 page opinion. “Apple and the Publisher Defendants shared one overarching interest that there be no price competition at the retail level. Apple did not want to compete with Amazon (or any other e-book retailer) on price; and the Publisher Defendants wanted to end Amazon’s $9.99 pricing and increase significantly the prevailing price point for e-books. With a full appreciation of each other’s interests, Apple and the Publisher Defendants agreed to work together to eliminate retail price competition in the e-book market and raise the price of e-books above $9.99.” While throughout this legal dispute, book publishers portrayed themselves as endangered curators of great literary work, what lies at the core of this case is the frightening reality that digital disruption of the book industry leaves publishers in a highly vulnerable and uncertain position. Even had Apple won this case on the publishers’ behalf (or prevails in its promised appeal), publishers will still need to figure out how to continue to add value in an environment where they no longer serve as the predominant gatekeeper, deciding which books get published, promoted and retailed to consumers. This is a legitimately scary concern, as exemplified by prior victims of technology-driven disintermediation, including Kodak, Blockbuster and Tower Records. So it is understandable that book publishers would seek legal relief from the inexorable erosion of their competitive position. But the ruling in this case was correct, in that accepting the position advocated by Apple, book publishers and the New York Times would require the willful suspension of belief in the intent of antitrust law and in the realities of free market competition as noted below:

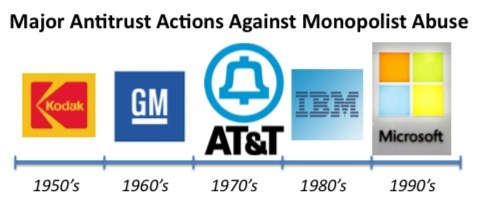

In the end, this anti-trust trial proved to be a slam-dunk case. The DOJ’s claims were backed up by damaging e-mails and phone logs establishing Apple’s and the publishers’ anti-competitive intent and by data that showed the incontrovertibly harmful consumer impact of their collusive behavior. The issue for Apple and publishers of course was never an overriding concern with what was best for consumers, but only what was best for them. This isn’t unusually callous behavior… it’s just business. Apple did not want to compete head on with Amazon in the retail market, and conspired with publishers who feared that Amazon would eventually demand lower wholesale prices, starting with e-books and eventually expanding to all books. To publishers, Amazon posed an existential threat. But the notion that publishers need to be exempted from broadly applicable antitrust constraints on collusive behavior to protect the status quo from the inevitable consequences of digital disruption, is an intellectually tenuous argument at best. The sad fact is that many aspiring authors would argue that the publishing industry has been retreating from its historically laudable role of promoting great literature and important non-fiction work long before the recent explosive growth in e-books. In this view, major publishing houses have generally made life harder for new and mid-list authors by collectively skewing their advances and marketing budgets towards blockbuster titles, often of dubious literary distinction. The logical corollary to this view is that the possibility of self-publishing e-books has opened more opportunities for more authors to get to market, giving more choice to consumers at lower prices. Some hard working, earnest (and often poorly paid) managers in the book publishing industry will undoubtedly take strong exception to this view of their noble profession and deeply believe that antitrust action -- if any — should have been brought against the monopolist evil empire in Seattle. But in the end, it is the marketplace and not the courts that will dictate the outcome of “the new normal” in the book publishing industry. If you have any doubt that even seemingly indomitable monopolists are not exempt from the need for continuous innovation and adaptive change with or without judicial restraint, consider the following. Each of the companies depicted below were accused at the height of their market power of monopolistic, antitrust behavior. Yet none of these companies were able to continue to dominate the industries in which they once held market shares of ~50% – 90+%. In the decades following government charges of antitrust abuses (some won, most lost), Kodak and GM went bankrupt, what was left of AT&T was sold off at a fire-sale price and IBM and Microsoft are no longer considered monopolist threats. More recently, Apple’s iTunes, which once looked invincible in the music download music business is now facing stiff competition from a number of streaming music providers, including Pandora, Spotify, Songza, Google and yes, even Amazon! So in the book industry, as in every other industry, every player — including Amazon — will have to continue to adapt their business models to deliver value in an industry subject to relentless change. Transient competitive advantages will come and go, but business outcomes will be ultimately be determined in the marketplace, not in the courts. |

Len ShermanAfter 40 years in management consulting and venture capital, I joined the faculty of Columbia Business School, teaching courses in business strategy and corporate entrepreneurship Categories

All

Archives by title

How MIT Dragged Uber Through Public Relations Hell Is Softbank Uber's Savior? Why Can't Uber Make Money? Looking For Growth In All The Wrong Places Three Management Ideas That Need to Die Wells Fargo and the Lobster In the Pot Jumping to the Wrong Conclusions on the AT&T/Time Warner Merger What Kind Of Products Are You Really Selling? What Shakespeare Thinks About Brian Williams Are Customer-Friendly CEO’s Bad for Business? Uncharted Waters: What to Make Of Amazon’s Chronic Lack of Profits What Happens When David Becomes Goliath…Are Large Corporations Destined To Fail? Advice to Publishers: Don’t Fight For Your Honor, Fight For Your Lives! Amazon should be viewed as a fierce competitor in its dispute with publisher Hachette Men (And Women) Behaving Badly Why some brands “just don’t get no respect!” Courage and Faustian Bargains Sun Tzu and the Art of Disrupting Higher Education Nobody Cares What You Think! Product Complexity: Less Can Be More Apple's Product Strategy: No News Is Good News Willful Suspension of Belief In The Book Publishing Industry Whither Higher Education Timing Is Everything Teachable Moments -- The Curious Case of JC Penney What Dogs Can Teach Us About Business Are You Ready For Big-Bang Disruption? When Being Good Isn’t Good Enough Is Apple Losing Its Mojo? Blowing Up Old Habits What Is Apple's Product Strategy--Strategic Rigidity or Enlightened Expansion Strategic Inertia Strategic Alignment Strategic Clarity Archives by date

March 2018

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed