|

A number of news stories have recently surfaced on lapses in management judgment of the worst kind: errors of omission and commission that have led to needless deaths. After hearing about the duplicity, cover-ups and lack of oversight at General Motors and the US Veterans Administration, one is tempted to ask how the culture and management mindsets in these organizations evolved to tolerate such egregious behavior? And these are only the latest cases in a long history of corporate misdeeds — e.g. Enron, Lehman, Cendent, HealthSouth, WorldCom — that raise the related question: what were they thinking?! In retrospect, even in the worst cases of fraudulent or reckless behavior, it is probably fair to say that the men and women behaving badly didn’t join a company with the intent to brazenly break the law or endanger innocent lives. More likely, they felt intense pressure to meet performance expectations, in a corporate environment where the downside risks of underperforming were perceived as higher than the likelihood of penalties for inappropriate behaviors. In short, such individuals probably slid into an immoral quagmire with very bad outcomes, one misdeed at a time. Many companies react to the glare of bad publicity by blaming one or two “bad apples” as the cause of their fall from grace. But this explanation is superficial and often masks the root cause: the corporate culture that tolerates, if not fuels employee misdeeds. Can Culture Be Changed? To her credit, General Motors’ CEO Mary Barra has acknowledged shortcomings in GM’s management culture that contributed to its failure to identify a fatal ignition switch design defect. In her testimony before Congress last month, Barra threw the “old GM” under the proverbial bus, citing an historical management mindset which placed cost savings over corporate responsibility. Barra pledged that the “new GM” has already begun to purge the demons of the company’s ignominious past. Eric Shinseki, United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs since 2009 is said to have inherited a “culture of fear” at the Veteran’s Administration. At the VA, some management officials allegedly gamed the system to artificially inflate performance statistics, protected by a corporate Omertà, where potential whistleblowers feared the organization’s longstandinghistory of retaliation. Can such debilitating cultural environments be reformed? The answer is yes, and with deceptive ease under the right circumstances. Yet cultural transformation remains devilishly difficult, where more often, bandaid solutions fail to reverse longstanding incentives and protocols that have promoted (perhaps unwittingly) dysfunctional employee and management behaviors. Take Ford, for example. When William Clay Ford, the fourth-generation family member to run the company, remarkably volunteered to abdicate his position as CEO in 2006 at age 49, the company was in perilous condition. Ford was on the verge of bankruptcy, its product lines were stale and poorly received, its international operations were in shambles, and it suffered poor quality, high costs, lagging technology and unimaginative styling. Ford lost nearly $15 billion in William Clay Ford’s last two years as CEO. Much of the blame could be attributed to Ford’s toxic culture, characterized by fierce turf battles, lack of collaboration and severe fault intolerance, all of which contributed to an unwillingness for executives to acknowledge management challenges or to participate in joint problem-solving efforts. It was not uncommon for example for Ford executives to purposely design cars for their own region in ways that would make them unsuitable for sale in other regions, lest another executive benefit. Shortly after Alan Mullaly (formerly head of Boeing’s commercial airplane division) took over as Ford’s CEO, he started a campaign to reform Ford’s culture. Under the banner “One Ford,” Mullaly instituted weekly Business Plan Review meetings with his direct reports where each executive was expected to assess the status of programs under their watch. Many observers attribute the beginning of the turnaround of Ford’s culture and business fortunes to one such meeting, early in Mullaly’s tenure, when the then head of US automotive operations, Mark Fields gave one of Ford’s new car development programs a red flag, under a Red/Yellow/Green evaluation system Mullaly instituted for his management reviews. As the episode has been retold, Fields’ colleagues were shocked. No one had red flagged a major program to a Ford CEO before (in this case, related to a balky tail gate latch design). Mullaly broke the stunned silence by applauding Fields for his candor and asking whether there was anything the Ford organization as a whole could do to help. This is the deceptively simple side of culture change. At most other organizations, this type of exchange between two senior executives would hardly be worth mentioning. But at Ford, it signaled a sea change in how management would behave and communicate. Honesty was applauded. Collaboration was the new norm. Mullaly consistently reinforced his expectations for a more collaborative culture in every management forum, and further reinforced desired corporate values by changing Ford’s compensation incentives. Before Mullaly arrived, employee bonuses were based entirely on individual and division performance, unwittingly encouraging fierce rivalries between executives in “competing” units. Mullaly instituted new incentives, where individual bonuses were more heavily dependent on overall corporate performance. As a result, Mullaly’s mantra of “One Ford” took on real meaning where it counts most — in employees’ wallets. Over time, the revised management behaviors at the top level of the organization filtered down through the workforce, influencing decision-making at all levels of the organization. After eight years at the helm, Mullaly is leaving Ford in great shape. Ford earned over $42 billion in the last five years. Surging sales of Escape sport-utility vehicles, F-Series pickups and Fusion sedans drove Ford’s U.S. sales up 11 percent last year. In China, the world’s largest car market, Ford now outsells Toyota, and Ford has even begun to see sustained market share gains in its historically weak European business. And, as an enduring testament to the cultural transformation he engineered at Ford, on July 1, Mullaly will turn the CEO reins over to Mark Fields, the first executive to raise a red flag in a Ford performance review meeting. Leadership Styles Time will tell whether the Mary Barra’s “new General Motors” has indeed mended its ways, but the new CEO has a tough job ahead. For one thing, Barra is a 33-year veteran of the old GM, including leadership positions in engineering groups responsible for vehicle design. Barra is very much a creature of the old GM that she now disavows. Moreover, Barra’s ability to forcefully communicate her new vision has undoubtedly been reined in by legal advisors, defending against pending lawsuits and recall actions that may cost the company billions of dollars. At the very time the new CEO needs to communicate with laser-like clarity, and to move with speed and purpose in transforming GM’s hidebound culture, Barra has been deliberate, cautious and slow, prompting a bitingly savage Saturday Night Live parody. One early action Barra did take, was to appoint a new Vice President of Global Vehicle Safety with “responsibility for the safety development of GM vehicle systems, confirmation and validation of safety performance, as well as post-sale safety activities, including recalls.” While on the surface, this appears to be a positive step, it leaves unanswered fundamental questions about whether GM has really addressed its management shortcomings.

As Apple noted at the time, the vast majority of iPhone owners didn’t experience mobile phone reception problems, and for the few that did (allegedly related to how users held their phones) a simple fix was to use a protective rubber bumper which Apple subsequently provided to customers for free. Nonetheless, when news of Apple’s “Antennagate” first broke, Steve Jobs abruptly cancelled one of his rare family vacations and raced back from Hawaii to Apple headquarters to personally lead days of intense management reviews aimed at understanding underlying engineering design issues and determining Apple’s corporate response. Within a couple of weeks, Jobs conducted an extensive press briefing on the causes and cures for Apple’s phone design issues. Less than a month later, Jobs fired Apple’s Senior Vice President of Devices Hardware Engineering. No new organizational entities were created to ensure Apple’s product design integrity. Jobs responded to the product quality issue with speed, decisiveness and action. While it is admittedly unfair to directly compare Barra’s and Jobs’ responses to product design problems, given significant differences in context, the fact still remains that the breadth, speed and authenticity of a CEO’s response to ongoing challenges is perhaps the most significant determinant of an organization’s culture. As such, Steve Jobs clearly left his mark on Apple’s organization and Mary Barra’s leadership impact is still work in progress. What About Your Company? If you are concerned about the health of your company’s culture, there are four leadership essentials that need to be in place to achieve an effective transformation.

Leadership matters.

0 Comments

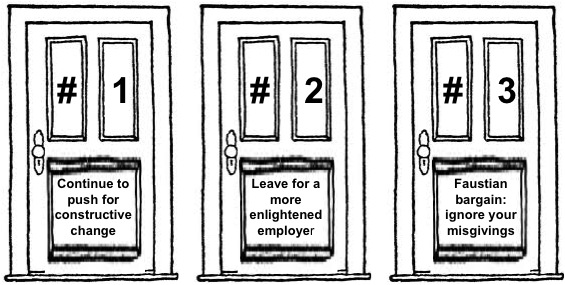

A recurring theme in my MBA course on business strategy this semester was courage. Executives need courage to create breakaway products that offer consumers a compelling value proposition in ways that are meaningfully different from competition. Such executives are not afraid to break from competitive norms; to go beyond the safe boundaries of incremental improvements. Think Tesla, Post-It Notes, Swiffer and Ikea. And executives also need courage to go all-in in ensuring that the company’s resources, assets and management incentives are fully aligned to support the breakaway strategy. Such executives become personally vested in, and identified with their business strategy, earning justified glory or job-ending rebuke, depending on outcomes. Think Nicolas Hayek at Swatch, Steve Jobs (second time around) at Apple and Dave Barger at jetBlue. The products and executives cited above provide inspirational stories of creative leadership, driven by leaders who live by the credo of “no guts, no glory.” But what are the implications for MBA graduates most of whom are about to enter the corporate workforce in entry level positions? They are not initially in a position to exert courageous leadership. Or are they? A guest speaker in my class near the end of the semester — entrepreneur, author, blogger Seth Godin — urged my students to approach their first (and every) job with the mindset to “make a ruckus” and “don’t be afraid to be fired.” In short, Godin was rendering themes from my course in very personal terms. Customer centricity and playing to win (as opposed to playing not to lose) are not just mantras for corporate leaders, but a code for all to live by. Now it’s easy for financially secure elders like Godin and myself to proselytize a message of personal leadership, driven by the principles of effective strategy without fear of rocking the boat. But what if you’re just feeling your way around a new job in a new company whose paycheck is critical to repairing your post-MBA balance sheet? How and where do you draw the line between pushing for constructive change and being a good team player in supporting your company’s current business direction? My short answer is there is no hard line, it’s a decidedly personal decision, but nevercompromise being honest with yourself about what you’re doing and why. It’s quite natural for students to approach their first post-MBA job with a combination of optimism and excitement. But once on board, what would you do if you find yourself becoming concerned and ultimately convinced that your company is headed in the wrong direction? You have three choices:

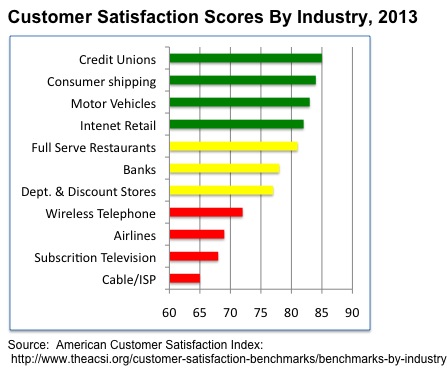

Here’s a hypothetical example to put this question to the test. Suppose you accept the premise that strategy should be formulated from an “outside-in” perspective — that is, the highest priority being to create and consistently deliver a compelling consumer value proposition. Internal capabilities, incentives and corporate policies should be aligned and managed towards supporting this end. That all sounds reasonable enough, but the reality is that companies vary widely in their commitment to operate in such a fashion. Watch what companies do, not what they say. Every company says that they value their customers, but there is a wide variance in perceived customer satisfaction across industries to suggest otherwise. For example, the exhibit below displays 2013 results from ACSI, a spinout from the University of Michigan, on customer satisfaction by industry on a 0-100 index scale. You probably shouldn’t be surprised to see that companies in the red zone — broadband/ISPs (e.g. Comcast), subscription television (e.g. Time Warner), airlines (e.g. United) and wireless telephone providers (e.g. AT&T Mobility) score quite poorly in delivering an appealing customer experience. There are a few bright spots (e.g. jetBlue), but by and large, companies in these industries have knowingly implemented business practices that extract revenue in ways that aggravate their customers. Now suppose you were hired in as a freshly minted MBA to manage Policy Assessment and Strategy for the Customer Service Group of one of the lower performing companies in one of these industries. After a few months into the job, with due diligence under your belt from proprietary company surveys, auditing customer service calls and internal management interviews, you report your initial findings to your boss. For starters, you confidently summarize what you believe to be the root causes of your company’s chronically poor customer satisfaction performance:

With MBA case studies still fresh in your mind on the success of truly customer-centric companies, you object, noting that focusing only on post-transaction customer complaints is inherently self-limiting and will ultimately reduce lifetime customer value. But your boss adamantly asserts that corporate management is well aware of the frequency and source of complaints received by customer service, and “they’ve done their homework to determine the profit-maximizing business model.” You’re tempted to press further — questioning the time frame for the analysis, or whether customer churn impacts have been fully incorporated in the analysis — but your boss’ mien signals this conversation is over, at least for now. So now what? You’ve essentially been asked to put lipstick on a pig, whose behavior is largely outside your control. You hopefully should get the opportunity to revisit your company’s broader business strategy questions, after having more time to gather evidence, to substantiate your recommendations and to get more savvy about internal politics. But the the possibility — and likelihood, given your current position in the company — still remains that you will be unable to instigate a personally satisfying course correction in the company’s strategy. Let’s say you’ve been at it for sixteen months, and it’s time to revisit doors #1, #2 and #3. |

Len ShermanAfter 40 years in management consulting and venture capital, I joined the faculty of Columbia Business School, teaching courses in business strategy and corporate entrepreneurship Categories

All

Archives by title

How MIT Dragged Uber Through Public Relations Hell Is Softbank Uber's Savior? Why Can't Uber Make Money? Looking For Growth In All The Wrong Places Three Management Ideas That Need to Die Wells Fargo and the Lobster In the Pot Jumping to the Wrong Conclusions on the AT&T/Time Warner Merger What Kind Of Products Are You Really Selling? What Shakespeare Thinks About Brian Williams Are Customer-Friendly CEO’s Bad for Business? Uncharted Waters: What to Make Of Amazon’s Chronic Lack of Profits What Happens When David Becomes Goliath…Are Large Corporations Destined To Fail? Advice to Publishers: Don’t Fight For Your Honor, Fight For Your Lives! Amazon should be viewed as a fierce competitor in its dispute with publisher Hachette Men (And Women) Behaving Badly Why some brands “just don’t get no respect!” Courage and Faustian Bargains Sun Tzu and the Art of Disrupting Higher Education Nobody Cares What You Think! Product Complexity: Less Can Be More Apple's Product Strategy: No News Is Good News Willful Suspension of Belief In The Book Publishing Industry Whither Higher Education Timing Is Everything Teachable Moments -- The Curious Case of JC Penney What Dogs Can Teach Us About Business Are You Ready For Big-Bang Disruption? When Being Good Isn’t Good Enough Is Apple Losing Its Mojo? Blowing Up Old Habits What Is Apple's Product Strategy--Strategic Rigidity or Enlightened Expansion Strategic Inertia Strategic Alignment Strategic Clarity Archives by date

March 2018

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed