|

We’ve all been inspired by stories of brilliant entrepreneurs whose game-changing ideas sparked in humble settings — e.g. a garage (Steve Jobs), dorm room (Mark Zuckerberg) or Milanese coffee bar (Howard Schultz) — blossomed into market-leading global enterprises. A new generation of entrepreneurs is now building companies that reached $10 billion in market value in record time (Uber, Airbnb, WhatsApp), posing grave threats to established industries. It would appear that the traditional bases of competitive advantage that used to protect incumbent market leaders – scale, operational experience, brand image, customer base, distribution, and financial depth –- can no longer withstand the onslaught of upstart entrepreneurs. This was the theme of Malcolm Gladwell’s recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants. In his retelling of the biblical tale of David and Goliath, Gladwell portrays David as a fearless, agile and resourceful fighter who defeats the dim-witted, over-confident and ponderous oaf, Goliath. Gladwell rebuts the common belief that David was an underdog. In this mismatch – and in a surprisingly large number of others – Gladwell asserts that leaders have liabilities that make them particularly vulnerable to brash upstarts. This should come as no surprise to students of business. History is replete with examples of profitable, market-leading corporations who were felled by smaller but more nimble and effective competitors. For example, when AT&T — the largest company in the US for much of the 20th century– failed to adapt to deregulation and the emergence of wireless technologies, it was forced to sell its dwindling assets for a fraction of its historical peak value to one of its former regional divisions. AT&T’s vulnerability as a ponderous, customer-abusing monopoly was bitingly captured in one of Lily Tomlin’s signature parodies, with the tagline: “We don’t care. We don’t have to. We’re the phone company!” GM, which also held the distinction of being the largest US corporation for decades declared bankruptcy in 2009, and only lives on today (in shrunken form) as the beneficiary of a taxpayer bailout. But GM’s management shortcomings are no laughing matter, as details of its willful disregard of fatal vehicle design flaws have recently come to light. Kodak serves as yet another example of how the mighty have fallen. The firm, which enjoyed photographic film industry leadership for over a century, peaking at a 90+% market share in the mid-1970’s, declared bankruptcy in 2012. Kodak is a poster child of Clayton Christensen’sdisruptive technology theory, which explains why large enterprises struggle to adopt innovations such as digital imaging. Are these isolated examples of bad management bringing down venerable institutions, or are market-leading corporations destined to be felled by disruptive upstarts, by aggressive attacks from traditional competitors, or by a combination of both? Conventional wisdom has increasingly tilted toward the latter: market leaders cannot sustain global competitive advantage over the long term. Take Apple as a case in point. A gloomy outlook has been predicted for the post-Steve Jobs enterprise by no less than a Nobel Prize-winning economist (Paul Krugman), one of the most influential business theorists of the last 50 years[i] (Clayton Christensen), a Wall Street Journal reporter and best-selling author (Yukari Kane), an SAP board member writing for Der Spiegel (Stefan Schulz) and 71% of respondents to a recent Bloomberg global survey who say that Apple has lost its cachet as an industry innovator. The reasoning behind these arguments that the mighty must fall is not limited to Apple, but stem from a broader belief that large enterprises inevitably lose their competitive advantages over time. But this viewpoint is not only flawed, but perversely could become a self-fulfilling prophecy of corporate failure. If management truly believes that long-term above-market profitable growthis impossible, the logical response is to protect and harvest current assets and customers for as long as possible. But such an approach — playing not to lose, as opposed to playing to win – only serves to hasten the decline of incumbent market leaders. The biblical Goliath may have been a ponderous oaf, but large enterprise CEO’s don’t have to be. Business Goliaths can continue to prosper if they maintain the same entrepreneurial spirit and adaptability that led to their success in the first place. Let’s explore the case of Apple as a case in point. On September 29, 2012, Apple reported record earnings, capping a remarkable three-year run during which the company grew revenues by 266%, profits by 406% and market capitalization by 280%. Already the most highly valued company in the world, few expected that Apple could continue its torrid growth rate forever. But as Apple’s margins and growth rate did begin to abate over the ensuing 18 months, many pundits declared this was a broader sign of the company’s expected erosion of competitive advantage, dooming Apple to average financial performance – or worse – going forward. For example, one of my esteemed colleagues at Columbia Business School shared this provocative point of view with MBA students: It’s very hard to dominate big global markets. Nobody has ever dominated electronic devices. Trust me, we’ve seen it in related industries for Sony, for Motorola and for Nokia. They’ve had nothing like the margins of Apple, and the margins of Apple have gone down by at least a third in the last 16 to 18 months. You can’t dominate a big market… Apple is going straight down the tubes! — Bruce Greenwald, Columbia Business School Why would a company that has repeatedly demonstrated extraordinary customer insight, innovation, design expertise, marketing prowess, high quality manufacturing and retailing excellence be headed “straight down the tubes?” I believe there are three fallacious arguments that underscore the belief that Apple, and indeed all market leaders, eventually must lose their competitive advantage and above-market financial performance over time:

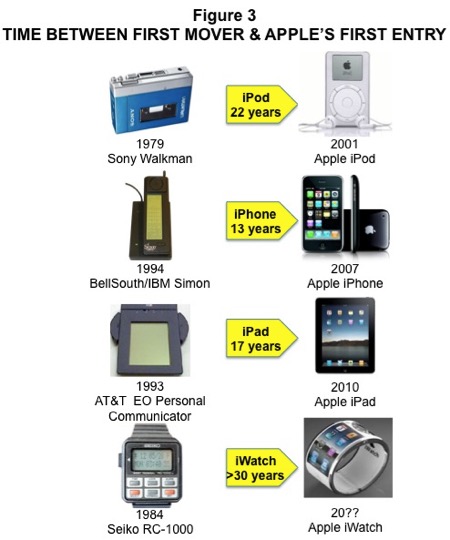

This law posits the obvious mathematical property that as a company grows, the incremental revenue required to maintain above market growth becomes ever larger. For Apple, whose revenue is currently $175 billion, the challenge is indeed daunting. For example, consider what would be required for Apple to grow it’s topline by 10% over the coming year, which while still above market average, is still only one-third of the compound annual growth rate the company achieved over the past five years. Growth of this magnitude would require the equivalent of adding the total revenue from companies such as Southwest Airlines or General Mills or US Steel to Apple’s current topline. No mean feat! Or think of it another way. Apple-watchers have been keenly anticipating the launch of theiWatch, in the intriguing “wearable technology” category. Characteristically, Apple has not been the first-mover in this emerging technology (nor was it in portable music players, smartphones or tablets), as smartwatches from Samsung, Pebble and more recently Google have been on the market for a year or more. But let’s give Apple the benefit of the doubt based on past success and assume that it achieves 10 times the industry sales of smartwatches achieved in 2013 ($712 million). At an assumed iWatch price of $299, this translates into annual sales of 24 million devices, generating just over $7 billion in revenue. As long as we’re being generous, let’s assume that each consumer also buys an average of $50 in apps each year for their slick new iWatch, of which Apple would claim a 30% revenue share. That would add a paltry $360 million in additional revenue (albeit at high margins). But the point here is that if Apple’s ability to continue to outgrow the market requires upwards of $17 billion of new revenue (and even more in the years ahead), it will take more than the vaunted iWatch to get the job done.[ii] It will undoubtedly be difficult for Apple to outgrow the market over the long term. But is it impossible? Absolutely not! The most definitive study on this issue was undertaken by the Corporate Executive Board in their landmark study of long-term growth rates. The CEB examined the performance of over 400 US companies that have been on the Fortune 100 list over the past 50 years, along with 90 non-US companies of a similar size. The authors concluded that approximately 13% of the nearly 500 large companies studied have been able to outgrow the market average for up to 50 years. So while outperforming the market over the long-term is a notably uncommon achievement, it is far from a mathematical impossibility. So where might Apple find its next growth wave, if not from the iWatch? There are several large opportunities that Apple may exploit that could fuel another round of dramatic growth. Opportunities include:

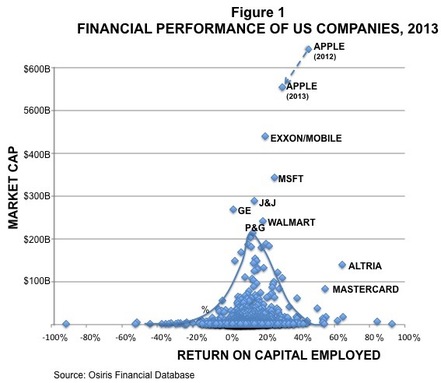

Under any circumstances, the assertion that Apple cannot continue to outperform the market because of the “law” of large numbers is pure sophistry – a case of simple mathematics posing as strategic thinking. The law of competition A second argument for why Apple is destined to decline falls under the rubric, the law of competition. According to this “law,” Apple’s historically sky-high returns on invested capital (ROIC) must inevitably revert to average levels for the following reasons.

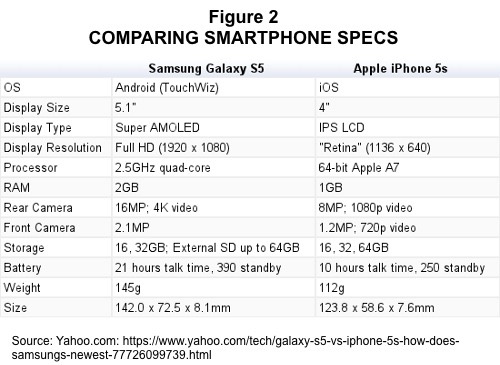

Many industry observers have also pointed to the loss of technological leadership in the smartphone/tablet market, and the four-year lag since the company introduced its last game-changing product (iPad) as further evidence of Apple’s inability to maintain the competitive advantage required to sustain high margins (see Exhibit 2). But the inexorability of the law of competition applied to Apple and other highly profitable corporations is fundamentally flawed on two grounds:

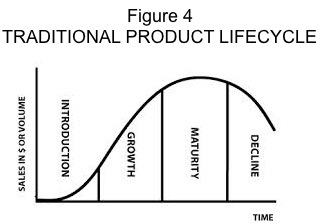

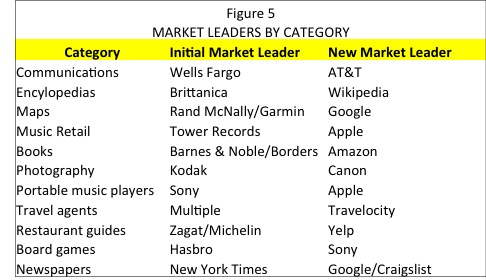

In fact, the [current smartwatches] do the opposite: they re-enforce all our old assumptions about the form, which is that you take your phone screen, make it small and stick it on your wrist. All I can think when I see them is: “Beam me up, Scotty!” And where’s the joy — or the desire — in that?… Admittedly, this has entirely to do with aesthetics, not functionality or engineering. But a smartwatch is an accessory, so aesthetics matters. Tech writers have been largely negative as well, noting the lack of useful functionality and confusing user interface of the current genre[iv]. Given these reviews, it’s not surprising that early sales in the smartwatch category have been disappointing. But if history repeats itself, Apple will once again set a new standard for style, form factor, capability, usability and market leadership when it launches its new iWatch, as rumored this fall. Critics who bemoan Apple’s late entry in this category as proof that Apple has lost its innovative edge in the post-Jobs era should remember that Apple’s unprecedented success with the iPod, iPhone and iPad came at least a decade after competitors pioneered product launches in these categories, as noted in Figure 3. The law of competitive advantage At the heart of the widespread conviction that large companies cannot sustain global leadership (marked by above-market growth and margins) is the underlying belief that the basis of a company’s competitive advantage inevitably erodes over time. A good starting point to examine the validity of this argument is to recall that all products and services experience aproduct life cycle. The familiar bell shaped curve shown in Figure 4 traces the trajectory of a new product through early adoption, rapid growth, maturity and eventual decline, driven by competitive technology advances and shifts in customer preferences. Schumpeter described this process as creative destruction over fifty years ago, and while the underlying dynamics are still compellingly true today, Downes and Nunes have argued that product life cycles have dramatically shortened due to a number of forces described in their recent book Big Bang Disruption[v]. Whatever one assumes about the duration of a product lifecycle – for example, in consumer electronics, successful products can come and go in less than a year – it is undeniably true that to sustain long-term market leadership, companies must consistently renew their product lineup with the “next new thing” in each of the categories in which they compete. This does not mean simply adding incremental improvements, which Christensen has noted propels most companies into a sustaining technology feature-function arms race. Rather, successful companies must rethink their consumer value proposition on an ongoing basis and be willing to consider entirely new product concepts aimed not only at current customers, but those poorly served by current offerings. And herein lies the challenge. In most cases, established market leaders struggle to disrupt themselves and eventually get overtaken by newcomers who bring radically different approaches to market that are often better and cheaper than existing products. The list of disruptive technology examples stretches back centuries and cuts across every industry sector. For example, as noted in Figure 5, Western Union’s telegraph business was decimated by Bell Telephone, which in turn gave way to Motorola/Nokia’s leadership in mobile handsets, which in turn got toppled by Apple/Samsung’s dominance of the smartphone market. Figure 5 lists numerous other cases where incumbent market leaders got toppled by newcomers who attacked with better product technology and/or superior business models. Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma explains that the reason why incumbents usually fail to disrupt themselves boils down to the strong tendency of large companies to:

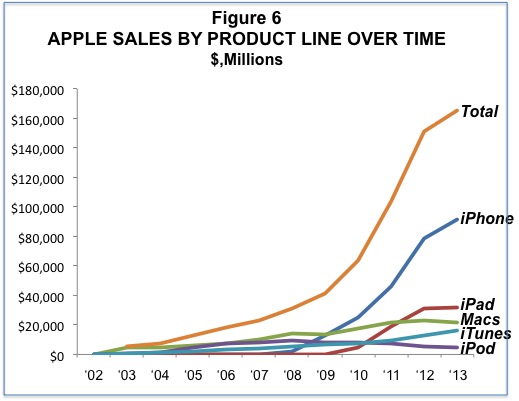

This is precisely what Apple and Amazon have done over the past 15 years. For example, Apple has continuously created new growth opportunities through breakthrough product innovation, sometimes at the expense of cannibalizing its existing products. This is illustrated in Figure 6 below, where the top line reflects the sum of sales from each of Apple’s main product lines over time. Similarly, Amazon’s exceptionally strong sustained topline growth (if not profitability) has been driven by relentless scope expansion and product innovation, often on initiatives with long-term payoffs and/or that have cannibalized existing product lines. Summing It Up The belief that business Goliaths will eventually lose their basis of competitive advantage stems from an implicit assumption that large enterprises suffer from strategic inertia. It is true that if a company (small or large) focuses more on defending current market positions than on renewing its basis of competitive advantage through meaningfully differentiated innovative new products and services, it will fail for all the reasons noted above:

Unlike scientific laws[vi], which describe intrinsic characteristics of our physical world, the business “laws” of large numbers, competition and competitive advantage can be broken by strong leadership. As Rita McGrath notes in her insightful book, Transient Advantage, winning companies can (and indeed must) repeatedly renew their basis of competitive advantage to sustain long-term profitable growth. It is admittedly not easy, and there are often strong headwinds that challenge corporate entrepreneurship. But exceptional CEO’s such as Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Howard Schultz (Starbucks), Marc Benioff (salesforce.com) and Fred Smith (FedEx) demonstrate that companies can continuously renew their bases of competitive advantage and achieve sustained profitable growth, notwithstanding the growing chorus of naysayers who assert that the mighty must fall. Whither Apple in the years ahead? Tim Cook’s leadership rather than immutable laws of large numbers, competition or competitive advantage will determine Apple’s business performance going forward. Time will tell.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Len ShermanAfter 40 years in management consulting and venture capital, I joined the faculty of Columbia Business School, teaching courses in business strategy and corporate entrepreneurship Categories

All

Archives by title

How MIT Dragged Uber Through Public Relations Hell Is Softbank Uber's Savior? Why Can't Uber Make Money? Looking For Growth In All The Wrong Places Three Management Ideas That Need to Die Wells Fargo and the Lobster In the Pot Jumping to the Wrong Conclusions on the AT&T/Time Warner Merger What Kind Of Products Are You Really Selling? What Shakespeare Thinks About Brian Williams Are Customer-Friendly CEO’s Bad for Business? Uncharted Waters: What to Make Of Amazon’s Chronic Lack of Profits What Happens When David Becomes Goliath…Are Large Corporations Destined To Fail? Advice to Publishers: Don’t Fight For Your Honor, Fight For Your Lives! Amazon should be viewed as a fierce competitor in its dispute with publisher Hachette Men (And Women) Behaving Badly Why some brands “just don’t get no respect!” Courage and Faustian Bargains Sun Tzu and the Art of Disrupting Higher Education Nobody Cares What You Think! Product Complexity: Less Can Be More Apple's Product Strategy: No News Is Good News Willful Suspension of Belief In The Book Publishing Industry Whither Higher Education Timing Is Everything Teachable Moments -- The Curious Case of JC Penney What Dogs Can Teach Us About Business Are You Ready For Big-Bang Disruption? When Being Good Isn’t Good Enough Is Apple Losing Its Mojo? Blowing Up Old Habits What Is Apple's Product Strategy--Strategic Rigidity or Enlightened Expansion Strategic Inertia Strategic Alignment Strategic Clarity Archives by date

March 2018

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed