|

There is a bitingly funny line in the 2007 movie The Bucket List in which Jack Nicholson’s character (a self-made billionaire) responds to a heartfelt compliment from his loyal business manager with the ultimate putdown: “Nobody cares what you think!“. Later in the movie, Nicholson smacks down his assistant yet again with the zinger: “I’d really like to say you’re irreplaceable, but I’d be lying.”  We laugh at such gratuitous boorishness, knowing of course that if we were the object of such scorn, it would be devastatingly hurtful. Cringe-worthy behavior has been a Nicholson comedic staple for decades. There’s an interesting backstory here with serious business implications. Critics were quick to bury The Bucket List with every pejorative in their Thesaurus when it first came out: “preposterous” (NY Times), “cheap and flimsy” (Miami Herald) and “a cloying … lazy low-grade product” (Seattle Times). But despite the critics’ scorn, The Bucket List went on to become an audience favorite, topping box office charts for weeks and grossing >$175 million for Warner Brothers. Moviegoers were in essence thumbing their nose at critics and telling them: “nobody cares what you think!” The declining relevance of movie critics underscores a broader shift transforming many industries: technology-enabled self empowerment. Think about it. The underlying value proposition for most companies is to sell a product or service that is too too complex, inconvenient or expensive for consumers to provide on their own. In this regard, consumers have historically been willing to pay movie critics (indirectly through their newspaper and television subscriptions or advertising eyeballs) for the valuable service of previewing and critiquing new film releases. But the internet has now created a platform for everyone to be a movie critic, and many moviegoers consider the “wisdom of the crowds” on sites like Rotten Tomatoes to be a more reliable guide, particularly if one can filter reviews to reflect individual preferences, as with Netflix’ and Amazon’s recommendation engines. Social network “Likes” have added yet another preferred alternative to the need for putative expert critics. Technology-enabled self empowerment has or is ravaging a number of other industries, including:

All the news that’s fit to print For historical industry leaders whose value proposition has been undermined by these disruptive technologies, the financial and emotional impact is no laughing matter. When customers begin in essence telling legacy market leaders that they no longer care what the company thinks (or sells), it’s terrifying. Take the New York Times for example. In 1896, the Times started carrying an iconic text box atop its front page embodying the hubris of a company laying claim to “All The News That’s Fit To Print.” During the ensuing 100 years, the Times had good reason to assume that consumers could not possibly serve as their own editors in ferreting out important news stories from around the globe. But in the post-internet era, a bevy of customizable search-driven applications now self-empower consumers to access news from a wide range of news sources and political viewpoints, including easy access to topics of personal interest that the Times maynot view as fit to print. Add to that the emergence of Twitter, which has often become the first to break current events, and it’s clear that the Times is now competing for customer attention in a very different world. What’s a company to do when their basis of competitive advantage that has served them so well for decades is severely undermined? Unfortunately, the most common initial reaction is paralyzing denial, fear and anger. What follows next ultimately determines whether a disrupted company can adapt and survive (possibly in smaller but sustainable form) or fail. IBM provides a good example of a company that not only survived but prospered after new technologies decimated their once-dominant mainframe computer business. After teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in the early 1990s, IBM shifted its business mix through acquisitions towards IT services, outsourcing and software to emerge as a stronger, considerably larger and more diversified company. Disruption has been far less kind to hundreds of brick and mortar travel agencies who were flattened by the rapid rise of online travel services. So how has the New York Times fared? To their credit, after experiencing early fear, uncertainty and doubt, the New York Times worked hard to remain relevant in the post-online news era. The company has pioneered a number of innovative online news features and successfully implemented the largest general newspaper paywall in the industry to supplement its profitable but steadily declining print newspaper business. While the internet has not been kind to its bottom line, online access has broadened the Times’ print audience reach by more than 25X. In Jack Nicholson’s parlance, more people than ever care what the New York Times thinks, albeit neither readers nor advertisers are willing to pay very much for the privilege. Revenues at the NY Times have declined 40% over the past six years, but the company has downsized sufficiently to secure a profitable future. Turmoil in the book industry The situation is a bit murkier for book publishers and booksellers, who are losing relevance (and financial viability) in a market increasingly driven by online purchases of paper and digital books. Technology self-empowerment is at play throughout the book publishing value chain, allowing authors to get to market without traditional publishers and readers to purchase books without bookstores. Reflecting the shift in bargaining power, one “Big 6” publishing executive recently told me: “it used to be that aspiring authors would damn near kill to be picked up by a major publishing house; now authors with self-publishing experience under their belt come to me with the question ‘what can you do for me?!'” In response, a number of traditional booksellers and publishing executives have reacted by decrying Amazon’s growing disruptive influence as evil, unfair and bad for society. In support of this view, publishing executives often note that their editorial prowess has helped bring great literature to market that might otherwise have never taken form. And booksellers are quick to point out their pivotal role in curating, displaying and recommending great reads to help struggling authors reach customers who would otherwise be unaware of promising new works. The problem with such arguments is that those dislodged by innovation in the book industry are conflating their own welfare with the marketplace as a whole. The fact is, more books are being written and read than ever before through channels which bypass the traditional book publishing industry value chain.

It is certainly true that talented editors working on behalf of traditional publishers have helped identify, refine and promote great literary works that have had considerable cultural impact. As cases in point, kudos to J. B. Lippincott who worked intensively with first time author Harper Lee in crafting the wildly successful To Kill a Mockingbird. Knopf’s role in bringing Julia Child’s masterpiece, Mastering The Art of French Cooking to market is another legendary publishing success story . And of course, Bloomsbury hit the financial jackpot when it took a flyer in 1997 on an unknown rookie children’s book writer named JK Rowling. But it’s important to note that each of these rock star authors was initially rejected by ten or more publishers before finally finding a gatekeeper — aka publisher — who allowed their work to get to market. For every Lee, Child or Rowling that was discovered in the pre-digital book era, there are scores of other great writers who lacked the luck, connections and/or perseverance to get their books published. These stories were never told. The gatekeeper role of publishers has changed of course in the post-digital book world where now any author can choose to self-publish an e-book or print-on-demand version with very little investment, and consumers can find promising new works by searching for topics of individual interest or by checking personalized wisdom-of-the-crowds recommendations on sites like Amazon or Goodreads. What does this mean for book publishers and booksellers? Book publishers will need to master new digital content skills to remain relevant in the post-digital market, offering authors a range of services that arguably can increase sales of books in multiple formats. For example, Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster recently publishedA Swing for Life by Nick Faldo, incorporating QR codes in the hardcover version, enabling consumers to view instructional golf videos on mobile devices. This tome is also available as an e-book, where multi-media clips are embedded directly in the text. Expect to see more multi-media, multiple format initiatives from traditional publishers and new entrants in the years ahead. There is also a continuing role for traditional booksellers provided that they restructure to the realities of a smaller base of loyal customers willing to pay higher prices for valued attributes. For example, Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Ore., has maintained an evangelistic core of customers enamored of the ambiance and expertise of their local bookseller, despite higher prices than charged by Amazon. Coda Companies that don’t want consumers to stop caring what they think or sell (and who doesn’t!) had better be prepared to continuously respond to shifts in how consumers prefer to get jobs done. While we can chuckle at Jack Nicholson at the movies, this is no laughing matter for incumbents in industries undergoing technology-enabled self empowerment. Many other industries are facing similar challenges, including higher education, routine medical services and licensed taxi operators. Is your company next?

2 Comments

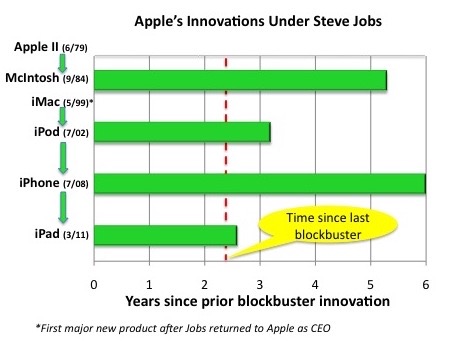

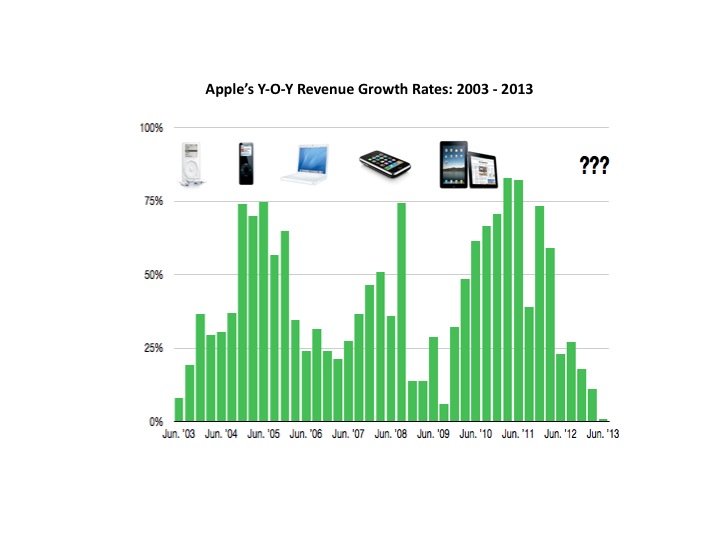

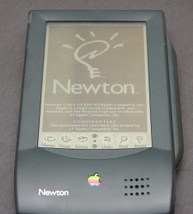

Question: how long should it take for a company to come up with an industry-changing, category-redefining, market-dominating new technology with sales of $10 billion or more. Answer: For the vast majority of companies, the answer of course is never. For Apple, the answer appears to be, not soon enough. It has been 2.3 years since Apple’s last game-changer — the iPad, which helped drive year-on-year profitable sales growth of 30+% (and mostly >50%) for ten consecutive quarters. During this astonishing run, Apple’s annual revenues climbed over $100 billion and its stock peaked at >$700 per share. But predictably — in fact inevitably — Apple’s growth rate has since slowed, and nervous investors have driven its share price down by 45% from peak. To add insult to injury, numerous pundits have declared that Apple’s uncanny knack for innovation died with Steve Jobs’ passing and its best days are clearly behind it. To be honest, it does feel like a long time since Apple launched a home run product, and it’s easy to believe that if Steve Jobs were still around, we wouldn’t still be waiting for some new form of technical wizardry. But a closer look at Jobs’ legacy for serial innovation suggests that such expectations are unreasonable. As noted in the exhibit below, during his two CEO stints at Apple, Steve Jobs never launched consecutive blockbusters in less than 2.3 years. In fact, it took six years for Apple to pivot from the iPod to the iPhone. From Apple II to the MacIntosh took 5.3 years. And even though Apple was working hard on tablets long before the launch of its smartphone, the iPad was launched 2.6 years after the iPhone. So why is Tim Cook being held to an unprecedentedly higher standard for product innovation? Perhaps because investors have been spooked by the sharp declines in Apple’s growth rates of late. But as shown below, Apple has always ridden a revenue growth roller coaster between game changing product launches. At least for now, what we’re seeing or not seeing from Apple is nothing new. The company’s future — as it always has been — will be determined by whether it can pull off yet another new product game-changer. Pundits and investors can have legitimately differing opinions on this question, but it is clearly too early to declare that Apple’s inability to launch blockbuster products over the past 2+ years somehow proves that innovation is dead at the company.

So what’s behind the title of this piece — that for Apple, no news is actually good news? There actually were two shreds of reassurance coming out of Apple’s otherwise mostly inconsequential quarterly earnings report this week. First, Apple announced surprisingly strong iPhone sales, exceeding analyst estimates for the quarter by 20%. That iPhone sales remained strong despite Samsung’s recent Galaxy S4 launch, supported by a breathtakingly lavish advertising budget, reaffirms just how strong the now venerable iPhone design really was. How large is “breathtaking”? Samsung’s global marketing expenditures for mobile devices is estimated to currently be on an annual run rate of $12 billion, more than the advertising spend by Apple, HP, Dell, Microsoft, and Coca Cola combined on all their products!. In that context, Apple’s market resilience is notable. Second, and more importantly, Tim Cook’s commentary during this week’s analyst meeting reaffirmed that the company has not abandoned Steve Jobs’ “outside-in” strategic perspective, which focuses the company’s energies on creating great products and customer experiences. In response to an analyst question on whether internal growth targets drive Apple’s product development and launch timing, Tim Cook responded: “The way I think about is, we’re here to make great products and we think that if we focus on that and do that really, really well that the financial metrics will also come… If you don’t start at that level you can wind up creating things that people don’t want.” While obviously, it would have been beneficial for Apple to have launched yet another blockbuster product by now in what would have been an unprecedentedly short amount of time, Apple’s greatest threat would be rushing to market with unimaginative products that tarnish its stellar reputation for product excellence. No one, starting with Tim Cook himself, claims he’s another Steve Jobs. But give the current CEO credit: he gets it. He is committed to sustaining Apple’s legacy for product excellence. Cook deserves at least as much time as his predecessor to tell if he can deliver. A former chief technology officer of Hewlett-Packard recently shared the profound observation with me that “the difference between a good idea and a great one is timing.” So true. While (too) much attention is often given to the dangers of being late to market — as HP assuredly was with its ill-fated and short-lived tablet computer — it can be just as deadly to prematurely enter a market before the technology, cost, or operational requirements are ready to deliver a viable consumer value proposition. To put the issue of launch timing in context, recall that every new product launch must overcome three inherent risks to become a market success:

Another example of a great idea in theory, that failed to deliver an attractive value proposition, is the Segway. Hailed as a revolutionary product that would change the world when first introduced by inventor Dean Kaman in 2001, consumers never could figure out why a $3,000 motorized scooter (banned from operating on most big-city sidewalks) made any sense. The world may have changed over the past decade, but largely without the ubiquitous presence of Segways. Overcoming risks On a brighter note, it is possible to overcome initially negative market reactions to new product concepts, as some of the most successful current products (or those intriguingly on the horizon) demonstrate. Consider the following:

The reasons underlying Apple's success with the iPad have been well documented, including thoughtful design and UI, technical refinement (e.g. battery life, screen resolution), the availability of hundreds of thousands of apps and a huge installed base of step-up iPhone users. All of this boils down to great execution and timing. Steve Jobs had an uncanny sense of not only what, but when to introduce new technology.

Rumors are flying that Apple has a cheap iPhone in the works. Coming on the heels of the iPad Mini, a growing chorus of groans is hitting the Twitterverse and blogosphere (to use two horrific terms) bemoaning that Apple is turning its back on Steve Jobs’ obsessive commitment to über product superiority; i.e. the best or nothing!

Perhaps. But consider this:

values. I’ve seen little evidence that Apple is moving in either of these undesirable directions. But like all great companies, the brand is only as good as its newest products. Roll on. |

Len ShermanAfter 40 years in management consulting and venture capital, I joined the faculty of Columbia Business School, teaching courses in business strategy and corporate entrepreneurship Categories

All

Archives by title

How MIT Dragged Uber Through Public Relations Hell Is Softbank Uber's Savior? Why Can't Uber Make Money? Looking For Growth In All The Wrong Places Three Management Ideas That Need to Die Wells Fargo and the Lobster In the Pot Jumping to the Wrong Conclusions on the AT&T/Time Warner Merger What Kind Of Products Are You Really Selling? What Shakespeare Thinks About Brian Williams Are Customer-Friendly CEO’s Bad for Business? Uncharted Waters: What to Make Of Amazon’s Chronic Lack of Profits What Happens When David Becomes Goliath…Are Large Corporations Destined To Fail? Advice to Publishers: Don’t Fight For Your Honor, Fight For Your Lives! Amazon should be viewed as a fierce competitor in its dispute with publisher Hachette Men (And Women) Behaving Badly Why some brands “just don’t get no respect!” Courage and Faustian Bargains Sun Tzu and the Art of Disrupting Higher Education Nobody Cares What You Think! Product Complexity: Less Can Be More Apple's Product Strategy: No News Is Good News Willful Suspension of Belief In The Book Publishing Industry Whither Higher Education Timing Is Everything Teachable Moments -- The Curious Case of JC Penney What Dogs Can Teach Us About Business Are You Ready For Big-Bang Disruption? When Being Good Isn’t Good Enough Is Apple Losing Its Mojo? Blowing Up Old Habits What Is Apple's Product Strategy--Strategic Rigidity or Enlightened Expansion Strategic Inertia Strategic Alignment Strategic Clarity Archives by date

March 2018

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed